Arrival Behind-The-Scenes: The Intersection of Language, Brain Science, and Time

“Like their ship or their bodies, their written language has no forward or backward direction. Linguists call this ‘nonlinear orthography,’ which raises the question, ‘Is this how they think?’”

I recently enjoyed watching Arrival from the Apple TV in my living room. (Warning: This post will contain spoilers!) All I can say is: Wow. I LOVED this film. It’s slow, intellectual, visually breathtaking and grandiose in theme – which is everything I love in a film. It reminded me of some of my other favorite movies that share these traits, including Tree of Life and 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The aliens' non-linear written language in Arrival. Art by Julie Silent/Julia Molchanova, via Behance, used with permission from artist.

One of the biggest themes in the film is the nature of communication and language (and how we might best communicate with aliens if we ever had the occasion to). The film explores how language impacts the way we think, specifically about time. Visual communication is also a key theme in the film. It turns out that communicating to someone who doesn’t know your language through text, spoken language and visuals all at the same time might actually be more effective than communicating in only one or two of these modes.

There’s research to back this up, too, as science comedian Brian Malow pointed out in a recent science communication workshop he gave at LSU (where I work). He stressed that relevant visual slides, when they complement an oral presentation (but NOT when they distract), can make a science talk more effective in terms of audience attention and understanding than the oral presentation alone. According to a theory of multimedia learning, “learners actively select, organize, and integrate verbal and visual information” such that coordinated text-based and visual media improve learning, including attention to and recall of complex information, more than text alone.

But let’s get back to Arrival. This film intrigued me enough to reach out to a few language and brain science experts to get their take on it!

I asked Rose Hendricks, University of California, San Diego cognitive science researcher and author of the blog What’s In a Brain, to tell us more about Arrival’s exploration of how language can shape our perception of time. For example, if we learned a non-linear language, would we think of time in a less linear way? I also asked “The Brain Scientist” Daniel Toker, neuroscience researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, to give us some insights on how the brain processes time.

Get ready for a mind-blowing (or time-blowing?!) Q&A about the alien-fantastic film Arrival!

Time. Stefanos papachristou, Flickr.com

“Language shapes how we think about time, and how we think about time shapes how we talk about it.”

Me: What were your overall impressions of Arrival, from a language or language science perspective? In the film, the protagonist learns an alien language and in the process (Spoiler!) starts to be able to see the future. Can our language really impact the way we think?

Rose Hendricks.

Rose: I saw the movie with my husband, who's a much bigger sci-fi fan than I. He liked it, but I raved about it the whole way home. Of course the details were made up (they were supposed to be!), but the idea that all the fiction grew out of was solid. Features of language, like the way it's written ("orthography"), and the metaphors in language (like "the future is ahead of us”) do shape the way people think. (Technically, the future is nowhere, but we often use words that describe space to talk about time.) Your mental timeline probably runs from left to right. But speakers of Arabic and Hebrew, for instance, hold mental timelines that run from right to left. (Tversky, Kugelmass, & Winter, 1991 is a seminal paper about this; another interesting paper that looks at vertical mental timelines in Chinese speakers who do or don't write vertically is here).

People's mental timelines tend to follow their culture's reading and writing direction. Whenever we're reading and writing, our eyes and hands follow a consistent motion - left to right, left to right - and that seems to drive the way we internally "represent" or imagine time. For this reason, I was pretty blown away that anyone who could read and write the heptapods' (the aliens in Arrival) cyclical writing started to think about time cyclically.

Another reason I was excited about Arrival was because a big conflict in the movie was the language puzzle. The film shed a rare light on the field of linguistics, showing that it's a super rigorous and complex field, which is often overlooked by people who see it as "just translation." The hero of the movie was not only a linguist, but a female one at that.

Me: Rose, you actually study the impacts of language on conceptions of space and time - how crazy is it that this movie touches your research so closely?! What kinds of things have you discovered through your research about how language influences our concepts of space and time?

Also I’ve been wondering – Is it language that influences how we understand time, or rather is it how we experience time as humans that has influenced the languages we have produced?

Rose: Yessssss, I was freaking out, or rather geeking out, internally during the movie and then externally for the week following. The chicken and egg problem you describe has actually been the focus of much of my research. The short answer is: both! Language shapes how we think about time, and how we think about time shapes how we talk about it. I've been working to empirically show both.

Most (maybe all) languages we know of tend to use spatial words to talk about time. Since time is not a thing we can see or touch, it's useful to have something concrete to grab onto when talking and thinking about it. But different languages use different aspects of space to talk about time. In English, the future is in front of us ("the times ahead") and the past is behind ("putting the past behind us”). In Aymara, an indigenous language spoken in South America, this convention is reversed: the future is behind and the past is ahead (this is the paper). This is how they talk about time, and their gestures suggest this is how they think about time as well.

But to know that language really causes people to think in consistent ways, we need a true experiment, and cross-cultural research is necessarily only quasi-experimental. We would need to randomly assign people to conditions, but we can't randomly assign them to be a native speaker of one language or another. To address this, we create new systems of metaphors and teach them to people in the lab. In some of my work, English speakers learn metaphors like "breakfast is above dinner" or "breakfast is below dinner." Then we measure their vertical mental timelines by asking them to make decisions about different events in time. People are faster to make decisions when we set the main task up to be consistent with their newly learned metaphors (e.g. the key on the keyboard they need to use to respond that one event happened earlier than another is above the key to respond that the event happened later), suggesting that they do have new mental timelines because of learning a new way to speak. A link to a paper on this is here.

We’ve also seen examples of our mental timelines becoming encoded in language. I mentioned that English speakers hold left-to-right mental timelines, but we don't always talk about it that way. It would be weird to say "Wednesday is to the right of Tuesday." BUT we found that members of the US military actually do use some left to right metaphors that civilians don't. In some military cultures, it's entirely normal to say "we'll push the meeting to the right from Tuesday to Wednesday." This is a reverse process from the one I've engineered in the lab – they already have common mental timelines, and it seems that they've put those into language (probably to reduce ambiguity, and perhaps also as a result of using tools like calendars that actually lay out time left to right). We still have lots of questions about what's going on there. Like, are there cognitive benefits of talking about time on the left-right axis? Why don't civilians do that? Instead we say things like "Wednesday's meeting was moved forward two days," which is ambiguous to English speakers (Here's some work on that).

Me: Are there any human languages that look similar to the type of written language the aliens use in Arrival (in other words, languages that are non-linear or where the written symbols convey meaning, not sounds?)

Rose: None that I know of. Most of the languages in the world don't have writing systems at all - they're just oral. But of the ones with writing systems, they can be written in different directions, but the ones we’ve documented are always linear. That makes the cyclical writing system even more perfect for this sci-fi film.

Luiseno Indian Pictograph. Matthew Robinson, Flickr.com.

Me: Daniel, can you tell us a bit about your research on the human brain?

Daniel: I study how the different parts of the brain share information with each other. Neuroscientists have a pretty good idea how the brain distributes information processing into many specialized regions, but we don’t yet know how it then integrates the outputs of those regions together. And it’s important to understand how the brain does this, because we think that this integration process is likely key to understanding perception and the nature of subjective experience.

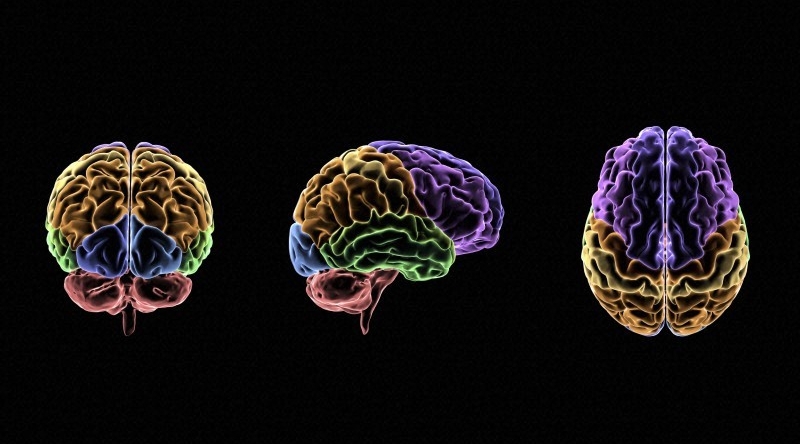

Areas of the human brain and their functions, illustration. Credit: Wellcome Images, Flickr.com

Me: What do we know about how the human brain experiences time? (Or how is "time" encoded in the human brain, and what parts of the brain process time?)

Daniel: The experience of time is a bit tricky, because we have to distinguish between the experience of time on the range of seconds from the experience of time on the range of minutes to hours (or even longer). If we’re looking at really short time scales, the key region that’s involved is the cerebellum. The cerebellum is way in the back and bottom of the brain, and is normally associated with fine motor control. The cerebellum has been shown to be involved in a range of tasks that require time information, such as rhythmic tapping or discriminating between different intervals. Damage to the cerebellum also leads to inaccurate estimations of short intervals. The mechanisms that allow the cerebellum to precisely coordinate our movements are likely the key to its involvement in short-scale time perception.

The experience of time on longer scales is quite different, and is less well understood. Some of the research I did when I was at Princeton was exactly on this question: how does the brain estimate the passage of time on the order of minutes? Our hypothesis was that people’s sense for elapsed time on these longer scales would be closely tied to how much the “stuff” of thought changed over time.

Imagine that you’re thinking about nothing but pasta for a few minutes. Behavioral research has shown that, in that case, you’re likely going to estimate less time having passed than if you were thinking about pasta, and then Italy, and then vacation, and then work, and then your bills, and then about your landlady, and then about your neighbors. That’s exactly what we found in the brain. The more activity changed over a given interval in a brain region called the entorhinal cortex, which is involved in forming new memories, the more time people thought had passed over that interval. That research was just published a few months ago.

Time passes more quickly if all you are thinking about is pasta... unless you are hungry?! Image credit: Popo le Chien

Me: Is it even remotely possible that the human brain could come to experience the future like we do memories of the past? Or is it possible that the human brain could perceive future possible scenarios better than it already does?

Daniel Toker.

Daniel: For us to be able to experience the future in the way that we remember the past, there would have to be causation going backward in time. The way we normally form memories is by brain activity getting “recorded” in a region called the hippocampus. Then, over a period of a few weeks, the hippocampus sends our new memories to our cortex for long-term storage. To be able to “remember” the future, future brain activity would have to somehow get stored in the hippocampus in the present. Seeing as how that would violate (known) laws of physics, I don’t think that’s possible, but who knows what the technology of the distant future will bring!

Me: In Arrival, the main character starts to dream differently because she is learning a new (non-linear) language, and this also is related to how she is perceiving time. What can you tell us about how the human brain perceives/processes time when unconscious/dreaming?

Daniel: It’s difficult to objectively test people’s sense of time while they’re dreaming, since normally researchers have to ask subjects to perform easily measurable tasks to measure their time perception. For example, researchers might have subjects reproduce an interval by tapping their finger.

But there’s an interesting study from the 50s that tried to see whether people’s sense of time while dreaming was related to how much time was actually passing in the real world. While there are rare anecdotes of dreams seeming like they’re lasting far longer than a single night’s sleep, a group of psychologists realized that they could get a somewhat objective estimation of dream time by getting people to incorporate external stimuli into their dreams. The researchers found that if they lightly sprayed subjects with cold water during rapid eye movement sleep, then that sensation would get incorporated into a specific dream event involving water. To get a sense of elapsed dream time, the psychologists would spray their subjects and then wake them up a minute or two later and ask them what they were dreaming about before waking up. Many of their subjects described a dream event that got them covered in water, and then described a sequence of events that could only have taken a minute or two to transpire before they were woken up.

This leads to the conclusion that dream time passes at more or less the same rate as real time. And that isn’t surprising, because the dreaming brain is almost identical to the waking brain. The difference between the awake and dreaming state is that your dream experience is being internally generated, rather than being driven by external stimuli. But the way the brain regions involved in time perception respond to the perceptual activity of a dream isn’t likely to be much different from the way they respond to the perceptual activity of waking life.

Arrival Fanart, by Julie Silent/Julia Molchanova, via Behance.

Me: Do we know anything about how animals (or theoretically aliens!) perceive time, as compared to humans?

Daniel: Other animals process time in a similar way to humans, at least at short time scales. For example, we know that psychoactive drugs affect mice’s perception of time just as it affects ours, which suggests that their brain processes time similarly to the way our brain processes time. [Paige: On an interesting, related note, in a recent talk on the science behind Finding Dory, LSU fish neuroscience researcher Karen Maruska busted the myth that fish only remember things for a few seconds at a time. In fact, she said, some fish remember things for weeks or months].

But my guess is that there are probably differences between humans and other animals in terms of how our biographical memories affect our sense of time over very long intervals. For example, does a century-old orca ruminate about the vitality of its youth? Does a dog feel like it has been years since it was adopted? There may be no way to test time perception in other animals at this scale, but it’s certainly food for thought!

So, while hypothetical aliens might be able to teach us a language that would cause some radical differences in our mental constructs of space and time, it’s unlikely that we could ever see or dream the future as Dr. Louise Banks does in Arrival. Our brains appear to process time in some consistent ways regardless of language (read Daniel’s intriguing responses about that in the Q&A above… or before, or to the left?? I don’t know anymore!)

If I had used cyclical language to write this blog post, would you have been able to better predict where this blog post would end?! How about Arrival – did you see it, and if you did, did you predict the ending?

Oh time, how elusive you are! And yet, sometimes painfully slow… hopefully not while you were reading this!!