The Road to Scientific Imagination: Connections between Science and the Movies

It might surprise you to know that science and Hollywood are intimately connected in today's society - and that this relationship has been a long time in the making. Only recently did the internet surpass TV as American's top source of science news and information. TV and movies have a rich history of bringing science and scientists into the public eye - sometimes with more positive effects than others. And scientists are increasingly taking notes from Hollywood storytelling to bring citizens closer to science and scientific knowledge making.

I've personally always had an interest in how science, science fiction and film are interconnected. In one of my favorite articles that I've written, I discussed how science and science fiction have exchanged ideas and pushed one another to new levels. But anyone interested in science in film and how they are connected would benefit from a discussion with two "giants" in this area, David Kirby and Amy Chambers! Both are researchers who study the portrayal of science and scientists in film, and the modern relationships between scientists and filmmakers.

You know what's next - a Q&A with David and Amy! They both write and tweet for the Science and Entertainment Laboratory (@SciEntLab). And the Q&A below is only a beginning of a conversation with these two researchers about science and movies that we plan to continue on Twitter tomorrow (Friday, October 21) at 10am central US time, hosted by the LSU CxC Science Studio @cxcsci. Have a read below, and then join us tomorrow on Twitter using the hashtag #CxCchat to ask your own questions about science and movies!

Don't miss this Twitter chat? A Storify re-cap will follow.

Nowadays, it would be shocking to find a movie or a TV show with significant scientific content that did not use a science consultant. - Dr. David Kirby

Paige: Many films, including Kubrick's 2001 and The Martian, have been so scientifically accurate (or at least plausible) because the film-makers consulted with scientists on the details of these films. Is this more common than it used to be?

David Kirby: It surprises people to learn from my book Lab Coats in Hollywood that filmmakers have utilized science consultants from nearly the beginning of cinema. Some of the more well known early films that utilized scientific advisors were the 1922 Lon Chaney, Sr. film A Blind Bargain, 1925’s dinosaur extravaganza The Lost World and Fritz Lang’s classic 1929 space film Frau im Mond.

However, the consistent use of science consultants is what I call a post-Jurassic Park phenomenon. Nowadays, it would be shocking to find a movie or a TV show with significant scientific content that did not use a science consultant. In general, audiences have become more sophisticated in the last two decades and they demand more complicated popular cultural products, including a more complex handling of scientific content. Contemporary audiences are no longer satisfied with previous scientist stereotypes nor with old portrayals of science as inherently dangerous.

Amy Chambers: It is far more common especially since Jurassic Park when the science became far more central to the storytelling process. When I first started to work in the field of science communication I was fascinated to learn about the breadth of shows and movies that use science advisors. There are obvious examples like The Big Bang Theory and also the movies of the Marvel Cinematic Universe – including the Thor films. When presenting on my research as part of public science events I like to put Thor’s Hammer (Mjölnir) in amongst the Jurassic Park toys and movie posters – it always leads to some really interesting discussions with both children and their parents about how important believable science is not only in terms of accuracy but also making movies entertaining.

Reconstruction of stop-motion scene of the destroyed car in the National Museum of Cinema of Turin, Italy. Image by Lewis Cozzi, Wikimedia.

Paige: How can scientists get involved with film consulting? What should they know before getting into this type of work (e.g. it's not just about making the film more scientific for science's sake?)

David Kirby: Many high profile scientific organizations - including the National Academy of Sciences’ Science and Entertainment Exchange, USC’s Hollywood Health and Society program and the Entertainment Industries Council - have developed initiatives to connect entertainment professionals with scientists. I think the Science and Entertainment Exchange does a great job. There are several elements that work well for the organization. It is well located in Los Angeles and has developed significant connections within the entertainment industry. Likewise, it draws legitimacy from its parent organization The National Academy of Sciences, which can open many doors. Most importantly, the program has shown concrete results that highlight how scientific authenticity can improve entertainment products. I also think it is important that they do not pressure filmmakers or TV producers to take scientific experts on board. They offer to pair up scientists with entertainment professionals and let them see the value of these collaborations themselves.

Amy Chambers: Just to add to what David said, I would point to these pieces we wrote on the subject with our colleague William R. Macaulay: Stories About Science: Communicating Science Through Entertainment Media, and What Entertainment Can do for Science, and Vice Versa.

Paige: Why is it important how science is depicted in film? What are the implications for science communication, science literacy, public engagement in science or science stereotypes?

David Kirby: Science and entertainment represent two of the most powerful cultural institutions that humans have developed to understand and explore their world. Most people are not scientists. Therefore, the public encounters images of science most often through depictions in popular culture. Several studies of science popularization demonstrate that its cultural meanings, and not its knowledge, may be the most significant element contributing to public attitudes towards science.

Images of science in movies and on TV can significantly influence public attitudes towards it by shaping, cultivating, or reinforcing these “cultural meanings” of science. By consulting on entertainment productions, scientists and scientific organizations can directly influence the ways in which films and TV programs depict science. It is more difficult for entertainment professionals to stick with negative stereotypes when they are increasingly collaborating with real-life scientists on their media productions.

In terms of the implications for science literacy, I think the increased use of scientists as consultants has motivated the scientific community to think more critically about the notion of scientific accuracy in movies and TV shows. It is just not possible to get 100% accuracy in movies. So, we should not be looking to films to improve science literacy. We do not want the science in films to be to be overtly false, but we should not expect film to teach people science. Scientific facts serve as the starting point for filmmakers who then use their own professional judgment to determine if, and how, these facts must be subverted during production. But the use of science consultants has improved science communication in a number of ways such as raising the profile of various scientific issues and contextualizing science within society.

Ultimately, science consultants can help filmmakers craft high-profile cinematic narratives that have the potential to excite the public about the possibilities of scientific research. That is a good thing.

Image by David Revoy / Blender Foundation, CC BY 3.0.

Paige: What aspects of scientific research and science film-making are similar? What aspects are so different that they may lead to misunderstanding between the scientific community and the film-making community?

David Kirby: The major similarity I found was that filmmakers were just as detailed oriented as scientists. The small stuff matters to them just as much as it does to scientists. The amount of work that goes into making sure that the smallest details of a set or a special effect are correct is staggering.

The biggest thing that surprised me was the fact that most filmmakers care a great deal about scientific integrity. The stereotype, of course, is that Hollywood filmmakers are money-driven hacks who will abandon scientific accuracy at the drop of a hat. In my interviews with both scientists and filmmakers I found that this could not be further from the truth. Sure, some filmmakers can be pretty cavalier with scientific integrity, but most filmmakers see the value in scientific authenticity. Filmmakers are professionals who take pride in their artistic creations, and the constraints of scientific realism provide them with challenges. It bothers most filmmakers when they have to abandon scientific accuracy, because it means they were unable to meet the challenges of creating an entertaining story within these constraints.

In terms of differences, I found that entertainment cultures differed from scientific cultures in some pretty substantial ways. For one, scientific cultures tend to be egalitarian academic communities. PhD students and post-docs can generally speak with senior researchers without much problem. Entertainment cultures, on the other hand, are not egalitarian communities. Instead I found that film crews have a very rigid hierarchy of superiors and subordinates. The problem for science consultants is that they do not have a specific place in this hierarchy. Scientists can often end up overstepping their bounds. I also found that some scientists felt that they needed to be careful about how they spoke with entertainment professionals, especially about the ways in which they phrased their advice about a script’s “bad science.” As professional science consultant Donna Cline told me, when she recommends dialogue changes to a script writer she does it carefully, “with tea and scones.”

Paige: Are there (historical) trends in how scientists have been portrayed in film?

David Kirby: Scientists represent the public face of science, so depictions of scientists can shape public perceptions of science. The popular cultural landscape used to be rife with negative depictions of scientists. But the last twenty-five years of films and TV show a significantly different picture. Contemporary portrayals of scientists have become more complex and far less negative than previous stereotypes. Whereas the mad scientist and the scientist as “powerless pawn” may have been the dominant stereotypes for most of the twentieth century, the last twenty-five years have given rise to the “hero” and the “nerd” as the dominant scientist stereotypes.

Depictions of scientists have shifted from being odd and evil to predominantly positive portrayals albeit with characters that are still eccentric and socially awkward. Even the most recognizable stereotype of the “mad scientist” has evolved and no longer resembles the maniacal, evil-obsessed one of decades past.

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley's Frankenstein. Public Domain image.

Paige: What are some of the key takeaways you have from your own research on the intersection of science and film, how science/scientists are portrayed in film, etc.?

David Kirby: My research shows very clearly that scientific expertise can be incredibly valuable in helping entertainment professionals create plausible, authentic and aesthetically appealing movies and TV shows. It is most useful if they bring scientists into their productions as early as possible. Not just for their expert knowledge, but also for what I refer to as scientists’ “expertise of logic.” Scientific training develops an ability to parse through small details, but it also gives scientists a capacity for understanding and seeing the connections within complex systems, a skill that can prove beneficial for screenwriters, producers and directors as they flesh out the structural foundations of their plots.

A common public perception of science is that it is devoid of creativity or that creativity hinders a practice built around objectivity. Yet, science is an incredibly creative process built around the skills of speculation, synthesis, integration and problem solving. Certain entertainment professionals, like James Cameron, bring scientists in as advisors very early during production because they understand that scientists’ expertise can be used to examine film and television scenarios holistically.

One of the main take-home messages from my research is that we get way too bogged down in the idea of "accuracy" when we judge movie science. I much prefer the terms authenticity and plausibility, which better capture how closely we think a movie's science represents real-world science without being bogged down with the unrealistic expectations of "accuracy."

We need to remember that films and TV shows do not generally succeed critically or financially because of the volume of accurate science they contain. Rather, movies and TV shows are successful when entertainment producers use science as a creative tool to make their texts visually remarkable, intellectually appealing, and dramatically engaging. The goal for science consultants should be to assist entertainment professionals in negotiating scientific authenticity within their own contexts of narrative, genre and audience. Just as scientists are scientific experts, entertainment professionals are “entertainment experts” who understand best how to deal with the constraints imposed by the media of film and television. Rather than inhibit creativity, working with a science consultant should compliment filmmakers’ skills at creating entertaining products.

A new film slated for 2017 tells the story of several historical female science figures.

Amy Chambers: Part of my research looks at the representation of women in STEM and the inclusion of women scientists in the processes of entertainment media production. This work is about gaining an understanding of how a more diverse representation of scientists on screen can directly influence the number of girls and women pursuing real-world STEM careers. I hope that the increasing volume of women scientists, on the small screen at least, will inspire young women to get and stay interested in science.

It is important to have women represented in fictional media as scientists from across the spectrum of science. By making women more visible in science settings – in both fictional and factual productions – inspiring images of science can be associated with women who are not only represented as smart individuals but as part of a network of diverse and complex professional women.

Paige: What is your favorite science-related film/movie?

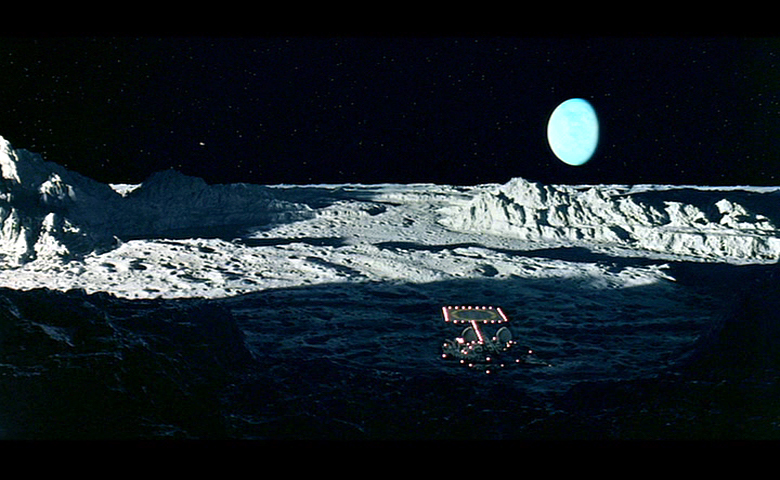

2001: A Space Odyssey Monolith Area. Image via Bill Lile, Flickr.com

David Kirby: I remember seeing Planet of the Apes as a kid and realizing that SF movies could have both exciting action sequences and be full of interesting philosophical ideas including debates about science and religion. 2001: A Space Odyssey is certainly the most scientifically accurate film made (for its time). Stanley Kubrick consulted with over sixty-five private companies, government agencies, university groups and research institutions.

I count myself in the company of Neil DeGrasse Tyson for my appreciation of the science in Deep Impact. Director Mimi Leder worked hard to make sure this film was more accurate than the other Near Earth Object film released in the summer of 1998, Armageddon. Although many people do not like Darren Aronofsky’s film The Fountain, I found it to be incredibly true to the scientific endeavor and about our need to find answers. I very much enjoyed The Martian for its tension and humor. Finally, while many people did not like the pacing (or the last half hour) of Interstellar I enjoyed its leisurely pace because it gave the film’s discussions time to breathe. [Note from Paige: Wow, The Fountain and Interstellar were my favorites. SF movie appreciation twins!]

Amy Chambers: My interest in science and cinema comes from my own love of science fiction cinema from the 1960s and 1970s. My PhD thesis included an extremely detailed analysis of the 1968 SF classic Planet of the Apes – despite spending years researching and dissecting the movie I still enjoy it. It takes a special film to keep you interested for so many years and to still find new things to talk about.

Most recently I loved the reboot of Ghostbusters because it gave us a major summer blockbuster with a diverse group of women protagonists (which is sadly rather radical in 2016) who are awesome scientists who save the world.

Paige: Anything else you'd like to add?

David Kirby: I study and write about movie science for a living. As such, family, friends and colleagues constantly ask me if I hate movies with “bad” science. To which I always answer: No! I hate bad movies regardless of whether the science is “good” or not! The true measure of a fictional film’s science is how effectively it uses that science to tell a unique and exciting story. I have a hard time with films where the science is not only completely implausible, but, worse, it is used to tell a boring or unoriginal story. The Arnold Schwarzenegger cloning film The Sixth Day is a particularly egregious example for me as were the films 2012 and The Core. I also find films with unrealistic or irrational scientist characters to be problematic which is why I hated Prometheus. Then there are films that make a total mockery of the “science” in science fiction like The Happening.

I actually created a new system for evaluating science in cinema that would not merely judge a film’s scientific authenticity on a scale from “good science” to “bad science,” but one that would also determine if the science was being used in novel and imaginative ways. We could hold the film to the same scale we would for any film regardless of how authentic the science is: Is it enjoyable? I wrote about this for Physics Today and they have used it several times to judge movie science. If people want to know more about my work on science and entertainment they can check out our website the Science and Entertainment Lab.