Better Left Alone: Flesh-eating Bacteria Thrive in Tarballs

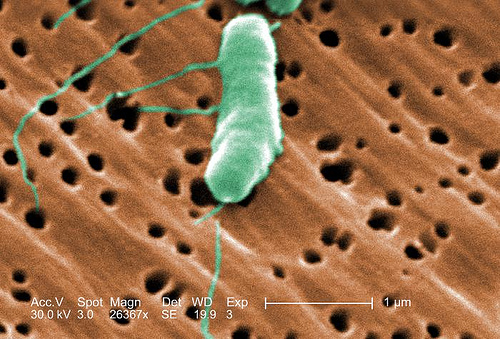

Dr. Cova Arias, professor of Aquatic Microbiology at Auburn University, and two of her lab members had rather disturbing results published in the journal EcoHealth last December, 2011, on their discovery of high concentrations of Vibrio vulnificus, also known as a type of flesh-eating bacteria, in tarballs.

What is surprising is that Arias’ findings haven’t received more attention from public health officials, given the implications of the research. Findings involving V. vulnificus should be a concern for public health authorities in coastal areas, given that in addition to causing severe wound infections, this bacteria is the leading cause of seafood-borne fatalities nationwide.

While many media stories have focused on either bashing beach clean-up efforts in the aftermath of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill, or hushing up the story completely, Arias’ group has clear data from tarballs and other forms of weathered oil on beaches in Mississippi and Alabama that could be valuable information for public health and future health research efforts. Especially in the aftermath of several reported cases of flesh-eating bacterial infections contracted from beaches and water in the Gulf of Mexico this summer, and warnings from the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals about flesh-eating bacteria found in Gulf waters, Arias’ findings are relevant and concerning.

I decided to have a Q&A with Dr. Arias, so that she could tell us in her own words the implications of her research findings on tarballs in the Gulf of Mexico. Before this research study, no published study had analyzed the bacteria that might be growing inside tarballs or other forms of weathered oil on beaches and in mashes in the Gulf.

From July to October 2010, Arias and her colleagues collected sand, tarballs and seawater from the intertidal of three beaches in Alabama and two in Mississippi, subsequently analyzing these samples for the presence of V. vulnificus genetic material. Arias found that V. vulnificus numbers are 10× higher in tarballs than in sand, and up to 100× higher in tarballs than in seawater.

Me: How did you come to study the presence of this bacteria in tarballs? Is this bacteria known to be associated with tar/oil?

Arias: I have been working with Vibrio vulnificus (Vv) since I started working on my PhD back in 93. I joined Auburn University in 2002 and soon after I started to work with Vv as one of the main concerns affecting the oyster industry in the Gulf. My Department has a lab in Dauphin Island where I had one student working on depuration of oysters [involves removal of bacteria from oysters] at the time of the spill.

I went there to see the effects of the spill and there were many tarballs on the beach in Dauphin Island. Actually, one of my colleagues who was with me at the time, asked me 'why don't you check if these have Vv?' so we did, and to our surprise, they contained high numbers of this pathogen.

Vv is a natural member of the Gulf coast environments. Vv is actually distributed worldwide, as long as the temperature and salinity [salt concentration] are right. Vv prefers warmer temperatures and brackish salinities, although it can survive in full-strength seawater.

Me: What were your major findings, and were these surprising?

Arias: We were surprised to see the high numbers of Vv in tarballs which compared to numbers found in oysters in during the peak season for Vv (summer). Oysters are filter feeders that tend to accumulate bacteria present in their surrounding waters, but we did not expect to find such high levels in tar. On the other hand, I guess nobody had looked before, so we didn't know what to expect.

Me: Do you know why V. vulnificus numbers might be 10× higher in tarballs than in sand and up to 100× higher than in seawater? What is special about the tarballs that might help them act as reservoirs for these bacteria?

Arias: Our hypothesis – which has not been demonstrated yet, we'll need to run more experiments – is that Vv is using the byproducts of the microbial communities that are degrading the tar as source of food. Based on the Vv genome, it is unlikely that this bacterium can degrade most of the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) present in tarballs, but it may be using byproducts from the bacteria who are actively degrading the tarballs. Basically, tarballs contain a much higher concentration of organic carbon (bacteria food) than sand or water.

Me: What are the implications of this finding for cleanup efforts and beach safety? Is this bacteria a threat to animal or human health when contained in the tarballs themselves, or when somehow released from tarballs into surrounding environment?

Arias: We don't know the answer to the second question, i.e. is Vv virulent when it is attached or embedded in tarballs? We'll have to use animal models to prove this, but as precaution, I would advise people to avoid being in contact with them, particularly if they have any kind of skin abrasion or open wound.

What we wanted to change with this study was the idea that tarballs are a mere nuisance (as NOAA published soon after the spill). The fact is that they do contain high number of bacteria and at least one pathogenic species. We only looked for one, V. vulnificus, but perhaps there are more. It may be that they have the same effect as a rotten crab on a beach, which also provides an excess of organic carbon. But while most people will avoid a rotten carcass, they may be tempted to touch a tarball.

Someone asked me once after I presented our data at a scientific meeting, what was the difference between having a dead crab and a tarball on the beach – basically, why was I making such a big deal about it? And my answer was: well, if you have a ton of dead crabs sitting on a beach that'll become a public health issue. I think public health authorities should monitor the presence of pathogens in areas where we still have weathered oil.

Me: How can this bacteria affect the environment and humans exposed to it?

Arias: Vv is a marine bacteria that probably plays an important role in the carbon cycle of estuaries and coastal environments. It's very abundant in our Gulf coast ecosystems particularly during the warmer months of the year. It's supposed to be there, it's not a contaminant.

We believe – several groups are working on it but we still need more data on this – that only a small percentage of Vv cells are pathogenic. In addition, not everyone is at the same risk of contracting an infection caused by this bacterium. There are some diseases such as cirrhosis [liver disease] that makes people more susceptible to it. Exposure to Vv by cutaneous contact, i.e. touching a tarball, can lead to severe wound infections, but you need to have a preexisting wound or at least a skin abrasion/cut in order for the bacteria to go through the skin.

Me: Is this the same bacteria that can cause 'flesh eating' skin infections? Can you talk to me about the safety procedures your lab has to use to handle these bacteria-contaminated tarballs?

Arias: Yes, sometimes Vv can cause severe wound infections that lead to amputations and in a few cases to death. People who fish or spend time doing recreational activities in the Gulf, particularly in summer, should be aware of Vv. Seeking medical attention as soon as the wound is infected is critical for a good outcome. We have detected Vv in the fins of many fish species that range in the Gulf as well as in bait shrimp.

Vv is considered a bio-safety level 2 microorganism, and we used appropriate methods to decontaminate everything that has been in contact with this pathogen.

Me: What are the future plans for your research, and how do you hope your current findings will inform current clean-up and research efforts?

Arias: I'm still trying to figure out a way to get research funds to continue this study. Unfortunately, two proposals that we submitted to the Gulf Research Initiative didn't get funded but I'd like to try again. Honestly, I don't know how our data will impact clean-up or other research efforts, but I hope it will translate into more public awareness on vibrios.

To learn more about Dr. Arias’ research, visit here and here.