Land of Desire: A Consumer Culture

"By 1929, after almost fifty years of growth and struggle, the modern American capitalist culture of consumption had finally taken root."

The following is a review of William Leach's book Land of Desire, an analysis of American consumer culture.

"By 1929, after almost fifty years of growth and struggle, the modern American capitalist culture of consumption had finally taken root."

The following is a review of William Leach's book Land of Desire, an analysis of American consumer culture.

The main point of “Land of Desire” is to describe the formative years and forces behind the culture of American consumer capitalism, to “illuminate its power and appeal as well as the tremendous ethical change it brought to America” (p. xiii). William Leach focuses on the creation of this culture, its production “by commercial groups in cooperation with other elites comfortable with and committed to making profits and to accumulating capital on an ever-ascending scale” (p. xv).

In Part I, Leach describes the commercial strategies designed to entice desire in the customer. He describes the rise of investment banking and giant retail corporations, department stores catering to a rising consuming middle class. He describes forces that led to businessmen’s fostering of the public’s “ability to want and choose” (p. 16). New manufacturing technologies and energy sources enabled mass production. Communication and transportation technologies enabled the “rapid movement of goods and money” (p. 17). The problem of distributing mass produced goods led to new methods of marketing to entice the consumer, including “advertising, display and decoration, fashion, style, design, and consumer service” (p. 37). Department stores prevailed in the retail wars of the 1890s.

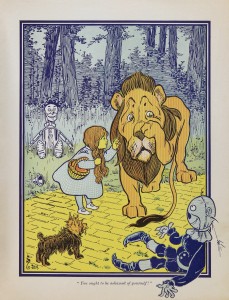

In the early 20th century, a “whole new aesthetics of color, glass, and light appeared on the American scene” (p. 38). Leach writes of the co-opting of new visual media including ad pictures, billboards, electrical signs and glass show windows for the movement of goods from retailer to consumer. Businesses targeted consumers through advertising campaigns and generally favored “eye-appeal” (p. 43) over the copy ad. Retailers hired commercial artists such as Maxfield Parrish to represent goods in widely appealing visual formats, to give goods “life” and “meaning” (p. 54). Parrish and other advertisers discovered “that pictures can attract attention, inspire a measure of loyalty, and excite desire” (p. 54). L. Frank Baum inspired a new display strategy in the glass show window that focused on how goods looked, “designed to foster year-round consumer desire” (p. 60).

Appeals to Christian ideas, corporate public image problems and merchants’ need to move goods contributed to the rise of service in 20th century America. Consumer service reflected the “pursuit of individual pleasure, comfort, happiness, and luxury” (p. 122). While serving a corporate image of public goodwill, service was at its core another strategy of enticement, designed “to awaken individualdesire” (p. 113). Visual display, service, central decorative themes and dramatic atmospheres reflected merchants’ efforts to appeal to consumer fantasy and to separate the world of consumption from the world of production. These efforts resulted in separation of the middle-class consumer from the hard-working lower-class production worker.

In Part II, Leach describes the rise of institutional coalitions and the role of these in shaping consumer culture. Art schools and universities began offering education in commercial arts and business administration. Museum owners and directors committed their cultural institutions “to the emerging prerogatives of consumer capitalism,” (p. 172) seeing images of the past as marketable goods. Government agencies helped commercial markets directly and indirectly, contributing to advertising standards and age segregation of customers. An Industrial Workers of the World pageant marked the collapse of a strike against silk manufacturers as “the pictured struggle” diverted workers “from the actual struggle,” (p. 189) in the words of Gurley Flynn.

Leach also explores people’s religious responses to the moral challenges of a new commercial society. New ethical compromises integrated consumer pleasure, comfort and acquisition into traditional Christian world-views. Mind-cure, an optimistic spiritual mentality that erased the lines between religion and commerce and embraced the dominant business culture, was a more radical response. It reflected the new “American conviction that people could shape their own destinies and find total happiness” (p. 227) through desire, consumption and abundance. Mind-cure influenced progressive political economists in 20th century America, including Simon Patten and his support of corporate capitalism and the “steady purchase of ‘new’ goods” (p. 239). Baum introduced into The Wonderful Wizard of Oz “a mind-cure vision of America quite at home with commercial development of the country” (p. 250).

In Part III, Leach writes of the rise of “Consumptionism” in the 1920s. Mass distribution infrastructure, business consolidation, a spread of chain stores and standardized advertising fed a mass “compulsion to buy what was not wanted” (p. 268). Investment bankers promoted merger activity in the mass consumer sector and secured the capital required for this activity. Bankers “saw in the expansion of what the banker Paul Mazur called ‘the machine of desire’ one of the keys to continual economic growth and profits” (p. 276). Mergers and bigger capital investment demanded “a new managerial angle to enticement” (p. 298) embodied in the idea of selling consumers their dreams. Consumer credit institutions, specialists in modern display strategies that targeted goods, fashion consulting agencies and public relations managers contributed to a new managerialism in mass consumer business.

After 1920, the federal government and large financial intermediaries helped form a new American mass consumer economy and culture. Leach shows how the U.S. Commerce Department under Herbert Hoover provided businesses with technical information and a public more capable and amenable to mass consumption of goods. Consumer capitalism influenced American culture throughout the 20th century, with non-commercial institutions and federal government continuing to support corporate power over consumption and consumer desire. However, Leach writes, insecurity and a declining standard of living in America may usher in a new era of increased consumer responsibility and “refusal to accept having and taking as the key to being or the equivalent of being” (p. 390).

This post is derived from an original class paper by Paige Brown for the LSU Manship School.