Scientists, Insta-Fix Thy Public Image

Scientists have a public image problem. Could Instagram be an answer? In this post, originally published here, I chat with social psychologist Susan Fiske to explore how scientists are perceived by others, and what we can do about it. To help change public perceptions of scientists, please check out my new Scientist Selfies project. Myself and a team of researchers are crowd-funding a research project to explore public perceptions of scientists who Instagram (and selfie!), and we need YOU.

Dr. Susan Fiske is Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology and Public Affairs at the Princeton University Department of Psychology, and known for her work on social cognition, stereotypes and prejudice. In 2014, Fiske and Cydney Dupree conducted a study looking at stereotypes of scientists compared to other groups, or how warm and competent scientists are perceived compared to other groups, based on occupation. They found that scientists, while competent, are not necessarily warm, and that’s a problem for scientists who need to or would like to communicate with broad audiences.

“Perceptions of scientists, like other social perceptions, involves inferring both their apparent intent (warmth) and capability (competence). To illustrate, we polled adults online about typical American jobs, rated as American society views them, on warmth and competence dimensions, as well as relevant emotions. Ambivalently perceived high-competence but low-warmth, “envied” professions included lawyers, chief executive officers, engineers, accountants, scientists, and researchers.” – Fiske & Dupree, 2014

Fiske came of age in the 1970s, in the midst of the civil rights and women’s rights movements, she says. She grew up in Obama’s neighborhood in Chicago, Hyde Park, which she describes as “emphatically integrated.” In her experience, moving to Boston for college was a bit of a shock when she realized it was far more segregated than what she grew up knowing. She also comes from a long line of suffragists and women’s rights advocates, so she was naturally attracted to the topic of how people stereotype others.

“What concerns me most is that people treat each other with respect, and with some degree of depth,” Fiske said. “You can’t have that depth with everyone you meet, such as the gas station attendant, but you can certainly respect everybody. I got into social psychology because I wanted to try to make the world a better place. But I realized that a person would be more credible if a person had data. It seemed to me that you couldn’t just have opinions about how to make the world a better place.”

As Fiske studied social psychology and learned more about how people form impressions about other people, she was struck by how often people use stereotypes as cognitive shortcuts.

“I got interested in stereotypes as a way that people form impressions,” Fiske said. “At the time, cognitive psychology and social psychology were starting to influence each other, and I came in at the ground floor of social cognition research, which enabled me to work on how people make sense of other people.”

In 2013, Fiske was invited to the National Academy of Sciences Sackler Colloquium on the Science of Science Communication (II), and based on her experience decided that she could provide data on how people make sense of scientists.

“I don’t do science communication,” Fiske laughed. “I do it only as a practitioner, by the seat of my pants, without having any knowledge about it. But I thought that [for the Sackler Colloquium], I should bring what I know to bear on science communication, and I know the persuasion literature, which says that communicator credibility is a function of trustworthiness and expertise, which seemed to be an awful lot like the dimensions I was already working with, including competence and warmth.”

Following the Sackler Colloquium, Fiske persuaded her graduate student Dupree to work with her on comparing scientists to other groups of people in society.

Fiske has a long history of studying warmth and competence.

“Those were data that we knew how to collect,” Fiske said. “You should work with the expertise you have, not pretend you have expertise that you don’t.”

“To be perceived as warm, a person must adhere to a small range of moral–sociable behavior; a negative deviation eliminates the presumption of morality–warmth and is attributed to the person’s (apparently deceptive or mean) disposition. By contrast, a person who is perceived as unfriendly might sometimes behave in moral–sociable ways, but the person will continue to be perceived as unfriendly and untrustworthy…” - Fiske, Cuddy & Glick 2006, Universal dimensions of social cognition: warmth and competence

Fiske and her colleague created a map of scientists’ warmth and competence compared to other groups. Scientists ended up occupying the same quadrant (high in competence but moderate to low in warmth) as CEOs, accountants and lawyers.

Figure from Fiske's slides at NAS Sackler, 2013.

Social scientists in the past (prominently Susan Fiske) have established general groupings of American social groups based on a two-dimensional graph. On one dimension is warmth, on the other is competence. For example, the elderly and disabled are generally seen as low in competence but very warm. The poor and homeless are seen as both low in competence and low in warmth. Christians, women and the middle class are seen as moderately to highly competent AND very warm. The educated and professionals are seen as moderately warm and highly competent. The rich, and scientists? As competent but not very warm.

“I was curious – I was pretty sure that scientists would not be seen as warm and fuzzy,” Fiske said. “I think we (scientists) actually came out better than I expected. The geek stereotype is not exactly positive on warmth, or social skills. I was pleased in the end that scientists came out as competent as they did, given all the evidence denial going on now. People seem to think we [scientists] know something.”

Scientists did not perform well on warmth, a key dimension of trustworthiness. However, the results varied slightly for words that can also describe a scientist, e.g. “professor.”

“Saying ‘professor’ results in greater perceptions of warmth than if you say ‘scientist,’ because being a professor involves teaching,” Fiske said. “That seemed interesting to me.”

At first, Fiske interpreted these results to mean that, potentially, scientists should act more like professors and teachers in enhance how warm and trustworthy they seem to non-expert audience. But when Fiske received pushback on this idea from a fellow scientist, Kathleen Hall Jamieson, when she suggested this at the Sackler Colloquium.

“She said that we couldn’t do that, because it is patronizing; people in the community that scientists are interacting with haven’t asked to be taught, and they don’t want scientists to talk down to them," Fiske said. "I thought that was a really good point. Now, the more I read about elites interacting with non-elites, the more I realize that we’re [scientists are] distrusted because we talk down. We say that we have the facts, and that non-scientists don’t have a right to have an opinion on these facts. And that’s not OK.”

In our Scientist Selfies study of how scientists might change public perceptions of their warmth and competence through images, one of the variables of primary concern is gender. What about female scientists? Do they fare better on warmth and competence scales than male scientists? Women are generally perceived to be warmer but often less competent than men. For a female scientist, does the fact that she is a scientist dominant social impressions? Or the fact that she is a woman?

Researchers including Alex Todorov have conducted experiments on the characteristics of faces that make them look warm and competent. Competence tends to be masculine and older, while trustworthiness tends to be female and younger.

Fiske says we really don’t know, but it likely depends on the context. Currently, she is working with one of her students on a study to explore what happens when you present people with groups that combine traits traditionally belonging to different quadrants on the map of warmth vs. competence.

“How do people form an impression of a blind CEO, for example?” Fiske said. “They might have to really think about that. Impressions of a female scientist would depend on the context. In a James Bond movie, she becomes the female side-kick, and it doesn’t matter that she’s a scientist. In a science fiction movie, her being a scientist probably matters a lot. And how she’s dressed matters. Which identity is more salient depends on the context – I don’t think you can say categorically what it’s going to be.”

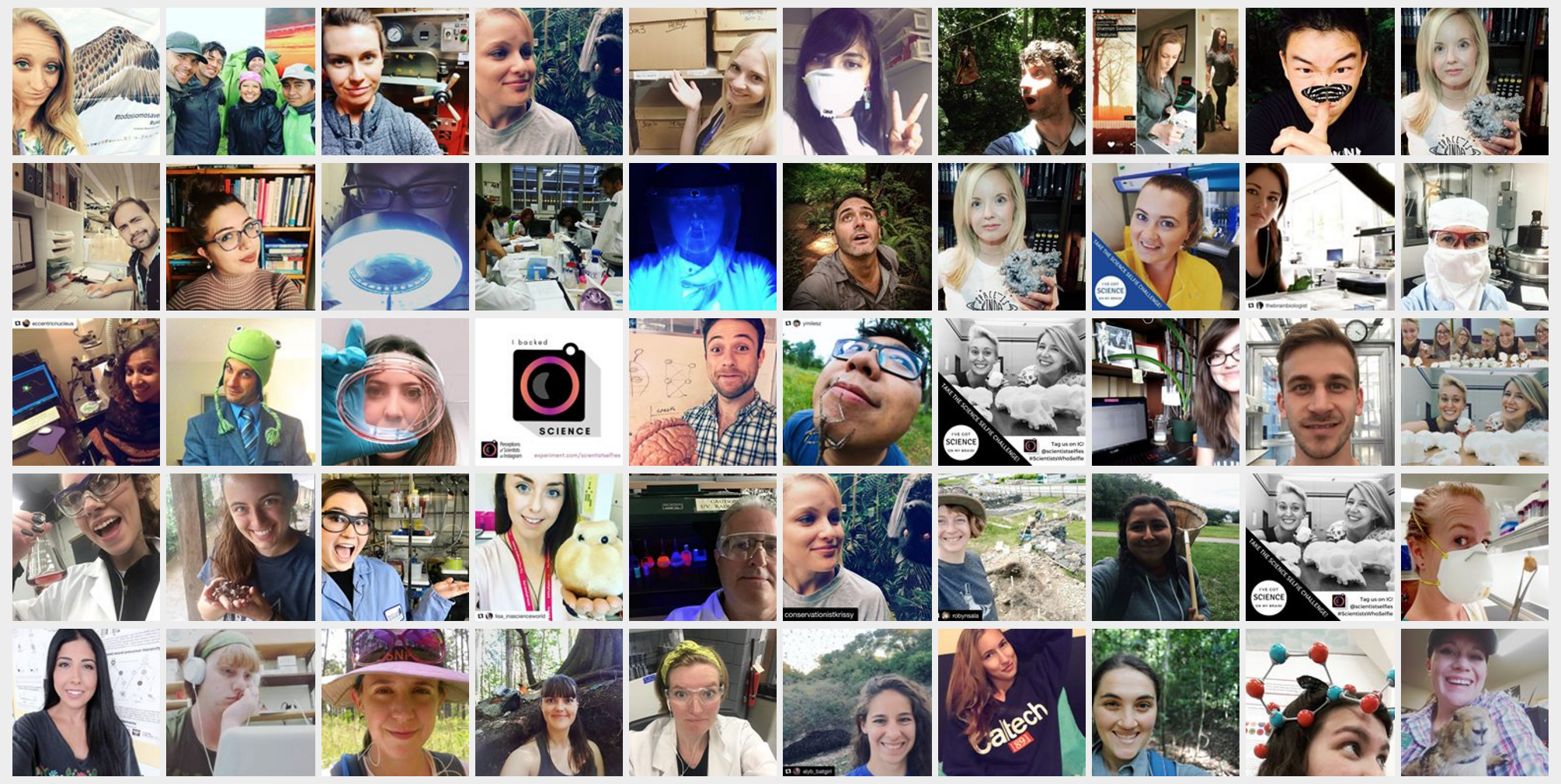

Scientists who Instagram, from an #LSUCure Instagram for Scientists online course in 2017

The stereotypes of occupations, Fiske says, are almost always inhabited by the default gender, and scientists are stereotypical male. For example, when Fiske tells people that she is a psychologist, many immediately assume she is a therapist.

“I have to explain that that’s not what I do, I do research. I can’t read their minds. And they are flummoxed. They don’t know what to say,” Fiske said.

On the positive side, there’s evidence that certain theory-guided manipulations can change stereotypes for the better.

“Competence is easy, it’s predicted by status,” Fiske said. “All over the world, people seem to believe in meritocracy, which strikes me as ironic because lots of people get high status because of luck, connections or circumstances they have no control over. Status is not actually a reflection of how smart you are. But if you want to change the perceived competence of someone, then you change their status.”

For example, immigrants can be described in highly different ways, based on status. On one side, some people might describe immigrants as the “dredges of their society” or “rejects who left because they couldn’t make it.” But if we say, “these are highly selective people, because you have to be extremely motivated to get here,” we can change the apparent competence of these same people, Fiske says.

For scientists, competence isn’t the issue. The issue is how warm and trustworthy scientists are (or aren’t) perceived to be. Perceptions of warmth fundamentally come from perceptions of either cooperation or competition.

Competition. Image by Chris Lott, Flickr.com

“To the extent that people see climate scientists as motivated primarily by trying to get their next grant, then people see these scientists as exploitative, as competing with the rest of society and untrustworthy,” Fiske said. “But if someone is a climate scientist because he/she cares about humanity, then people see them as having cooperative intent, and as being warm and trustworthy.”

Screenshot from #ScientistsWhoSelfie

Based on how perceptions of scientists’ warmth are related to perceptions about their cooperation or competition with society, one way to make scientists warmer could be to have more people tell stories of why they went into science. A researcher who tells a story about going into biology based on a passion or love for animals may be warmer than one who doesn’t tell this story.

It may also be important for scientists in the public sphere to stay away from prescribing policy based on their research findings, but instead present various routes or plans of action informed by their data.

Screenshot from #ScientistsWhoSelfie

I also asked Susan whether scientists on social media, scientists who present themselves publicly and are willing to engage people, might help break down stereotypes about scientists as being relatively cold and unsociable. It turns out that that we can target stereotypes in different ways. Imagining a spectrum, on one end we can tackle the overarching, general stereotype about scientists and how competent and warm they are or aren’t. On the other end, we can work to humanize and individual specific scientists, telling their stories to separate them from stereotypes about the group(s) they belong to.

“Anything that humanizes and individuates people gets the other person [the viewer/reader] away from stereotypes,” Fiske said. “You can try to change the [brutal and monolithic] stereotype of the group as a whole, or you can try to individuate a particular person, for example by saying ‘this person is more than a scientist; this person is a person who loves cats, or likes to go hiking, or likes to dance.' That’s a way of humanizing individual scientists.”

Humanizing scientists is where our Scientist Selfies project comes in. There's good reason to believe that scientists who share their scientific work on Instagram through visuals that include not only the science, but also their own faces, may elicit greater perceptions of warmth and trust from viewers. (As long as they aren't perceived as narcissistic or seeking attention for personal gain.) By interacting with viewers through comments on their Instagram posts, scientists may also send a message that they are open to discussion, sociable, cooperative and trustworthy.

Humanizing individual scientists may only change how people ascribe group stereotypes to those individuals. However, if you can individuate and humanize enough scientists, then people realize that scientists are varied, they aren’t all the same, thus breaking down the group stereotypes.

“If you can get people to realize that there’s a lot of variability in who is a scientist, then it’s harder to apply a general stereotype to scientists.”

No two scientists are the same.

Then, there’s something in between of individuating scientists and changing the group stereotype. Here, we can help people start to see that scientists aren’t all the same; that there are different types, or sub-groups, of scientists, such as social scientists, physicists, geologists, etc. Sub-grouping people is a step in the right direction away from general stereotypes, Fiske says, but isn’t necessarily the ideal.

“The best is when you get people to see, geez, there’s a lot of variability in [scientists], I can’t generalize too much," Fiske said.

Fiske complimented the #ScientistsWhoSelfie campaign for this reason. (Yay)! “I liked your display of all those [scientist] selfies, because it says, ‘Wow, look at all the variety, look at all the different kinds of people who are scientists.'”

Myself and a team of researchers and Instagrammers are excited to be conducting a study that will reveal more about how people perceive scientists who Instagram, how how various characteristics of those Instagram posts (gender, age and race of the scientist, lab or field environments, presence of a smiling human face, presence of interaction, etc.) might shape public perceptions. Can many Instagram posts created by scientists begin to change overall stereotypes of scientists held by Instagram users, if they follow these scientists? That's a question our team hopes we will at least set the foundation required to answer.

Inspired by our project? Help us conduct our experiments among a larger U.S. population and share the results widely by backing our project here! We need your help to make our goal! By backing our project, you'll get access to all of our updates and preliminary data, tutorials and guides on using social media effectively to share science and promote positive images of scientists, and you can claim cool perks!

Take a science selfie and post it to Twitter or Instagram using the hashtag #ScientistsWhoSelfie!

Selfie or bust!