What ASL is teaching me about effective science communication

For a little less than a year, I’ve been learning American Sign Language (ASL). It’s hard to describe how learning this language is inspiring me and enriching my life — not least because I’m developing wonderful friendships with Deaf coworkers and scientists! I was bilingual at a fairly young age, spending time going to public school in France and learning French. That experience opened my mind to other ways of living and other cultures. But I really do feel that learning ASL is doing something more; it’s opening up new pathways of thinking, particularly visual thinking, that are making me question the ways my first language leads me to think and allowing me to express myself in a completely new way.

As I learn ASL, it’s also natural for me to start thinking about how science is communicated in this language. Not only is science communication deeply embedded in my lens on life, but I started learning ASL to be able to communicate with a Deaf scientist coworker, so the topic of science in ASL comes up a lot!

ASL is its own language. It is not English. It is an incredibly visual language, often literally “showing” as opposed to “telling” and often using visual metaphors for various objects and concepts. In this way, I think it is really a very unique language. And when it comes to scientific research on things you can’t see with the naked eye — from micro-scale phenomena like cell biology and genetics to large-scale phenomena like environmental patterns, I think ASL has many unique advantages over spoken language!

Imagine having the power, without needing something other than your hands to draw with or needing expert drawing abilities, to show complicated concepts or processes in a visual space. You could explain “invisible” scientific concepts visually to someone at any time using only your hands and body. I imagine it like “Dance your PhD” on steroids — if only dance were a full-fledged language. How much easier is it to show what the inside of a cell looks like, or how a mitochondria produces ATP, versus describing it only in words? This is something that ASL can do that spoken and written English can’t, at least not without the complements of graphics and art.

There’s a growing field of research (in English) on how visuals and art can improve understanding of science and complex scientific topics. It’s a relatively young body of research, but it has found many benefits. Of visual science communication for science learning and discovery. Visual representations of scientific concepts and phenomena, from photographs to diagrams to visuals of molecular models, have long been a key aspect of the scientific research and discovery process. Take the discovery of the structure of the DNA helix, which would not have been possible without Dr. Rosalind Franklin's X-ray diffraction photos. Visuals unlock otherwise “invisible” scientific knowledge.

But visuals are also instrumental in science communication and education, enhancing interest in, recall and understanding of scientific concepts. Research shows that “visualization decreases the cognitive load and therefore lowers the total cognitive steps necessary” in grasping abstract concepts and understanding how objects like molecules fit together and interact in space. Visual explanations make science more accessible and improve learning. Art can make science less daunting and more approachable, engaging people’s emotions as well as their intellect in understanding the implications of scientific findings for example. Art can encourage creative thinking and problem-solving in science.

In short, hearing communication scholars have slowly collected evidence to support initiatives that communicate science in emerging visual forms like videos, comics, data visualizations and VR. But before much of this evidence existed, Deaf scholars had already established the benefits of visual communication. ASL users have been literally growing up using a completely visual language to better understand science and the world around them.

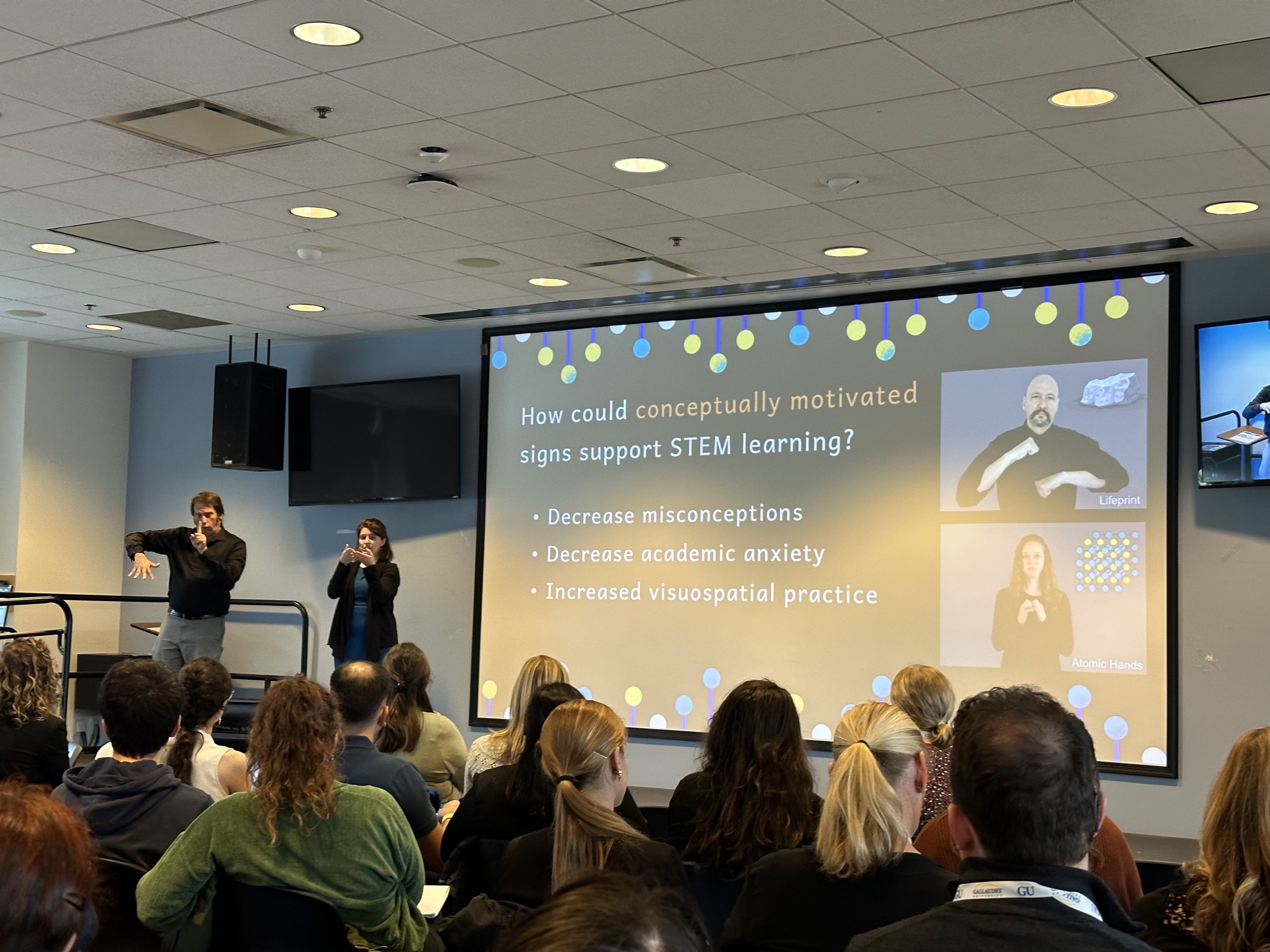

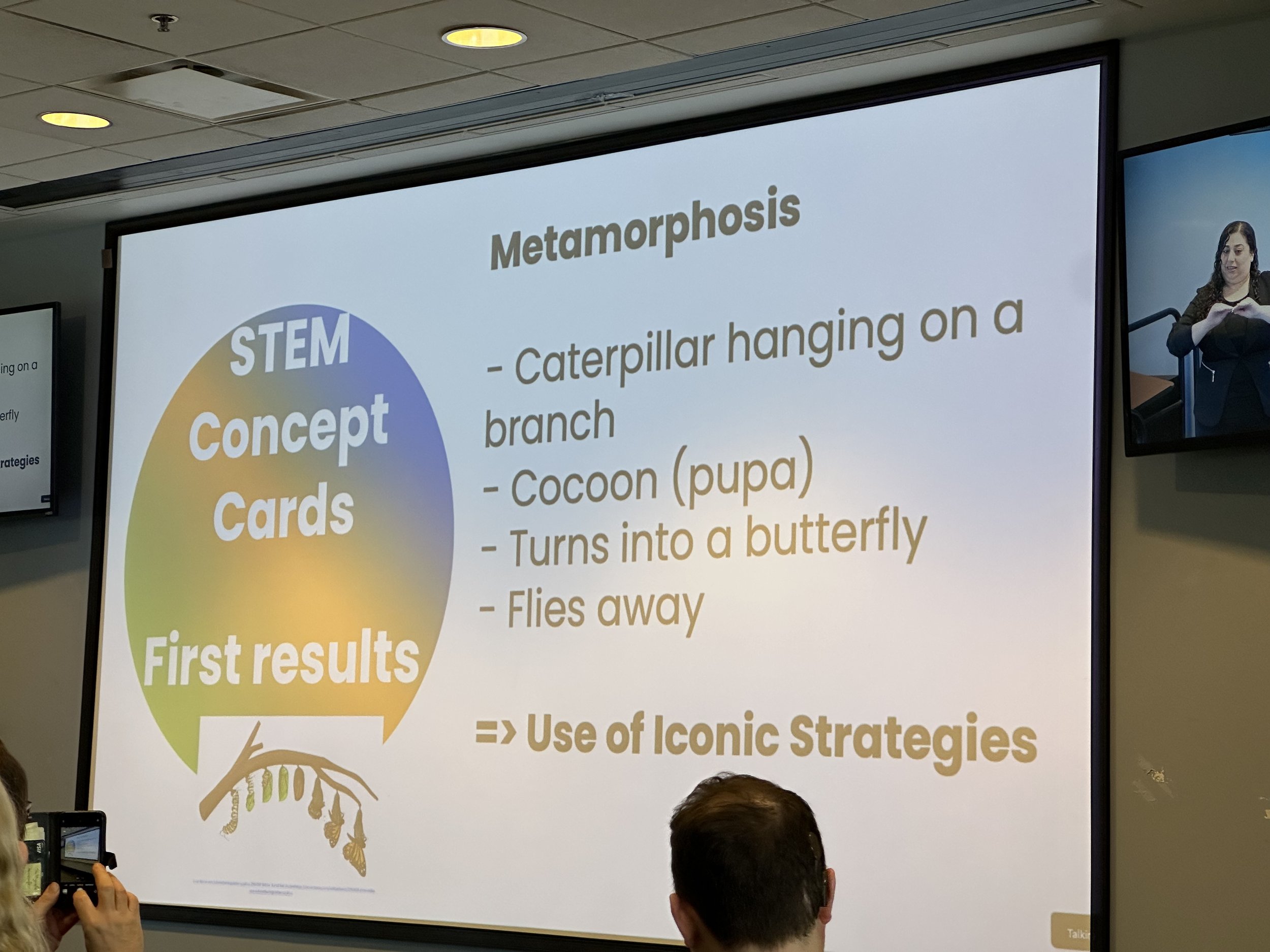

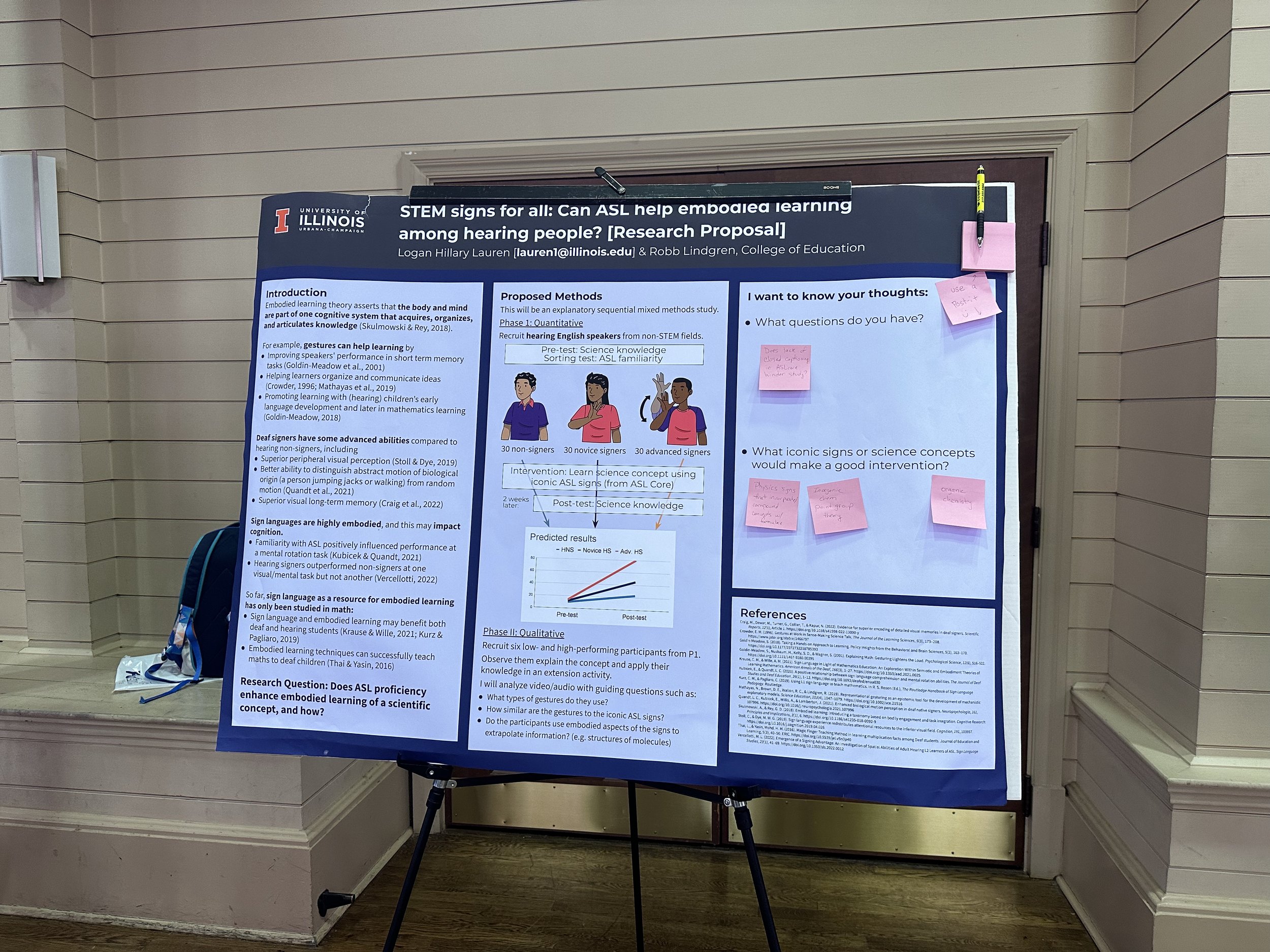

A gallery of images from Gallaudet STEM Sign Language Summit

I recently attended a STEM Sign Language Summit event at Gallaudet University. I realized that Deaf scholars in education, science and communication fields have known and studied the benefits of visual and sign language-based communication in STEM fields for many years now. They’ve found that embodied learning experiences – such as translating a scientific idea into visual space using sign language or experiencing a scientific object or concept through virtual reality – can improve learning. They’ve also found that deaf individuals have better visual acuity and may learn better through visual embodied experiences.

I know that personally, I’ve never been more interested in sea turtle conservation work than seeing a Deaf marine biologist tell the story of watching sea turtles hatch in ASL! There’s nothing more transfixing than watching a story like that being told on stage with sign language – because the presenter was literally “showing” what happened and what she learned about sea turtle biology in the process.

Now let’s revisit the scenario you imagined earlier, where you can communicate any aspect of science you want in a visually rich way using just your hands. But now, consider opting instead to just fingerspell all the jargon and scientific (English) language instead. Unfortunately, this is what happens a lot in contexts where ASL interpreters without scientific backgrounds are interpreting for Deaf scientists and science students. It’s like creating a text-heavy or text-only graphic and calling it a visual aid. It misses out on so much of the unique power of a visual mode of communication.

A lack of science communication in ASL created by and for deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals presents a barrier to exposure to and success in scientific education and research. Deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals may end up feeling unwelcome in STEM fields, and the benefits of learning about science in ASL are often overlooked.

Thankfully, there are growing efforts in the Deaf community to create new signs for scientific terminology. Best practices for creating these signs involve interpreting the underlying meaning of these terms, not just translating them word-by-word or letter-by-letter into ASL. Take “neuron,” for example. A recently created sign shows what a neuron is and even hints at how it transmits electrical signals. This is referred to as iconicity – a sign that looks like the object or concept being communicated.

It’s critical that deaf individuals be the ones to create new signs and interpretations of scientific words and concepts in English. Otherwise, you might get ASL translations of cater instead to English and hearing views of the world. Like signing “butterfly” as the sign for “butter” and then the sign for “fly”. But those signs already have visual associations for ASL users, as they do for us in English. Think how much more mental work is it to interpret the combination of two separate words (or signs) that each have their own separate meanings from the object we intend to communicate. How much simpler to show – “iconically” – what we really mean?

A visual of a butterfly and “butter” + “fly”

ASL sign for butterfly

There’s evidence that ASL sign iconicity helps with learning abstract concepts and remembering the new words for them. Iconic signs “help the learner to ground the labels for abstract concepts onto a concrete source.”

We all process visual information much more quickly than we do non-visual information. An ASL user seeing the sign for “butterfly” might be able to visualize the concept even more quickly than a hearing person who hears the word “butterfly” and then has to pull the related image from memory.

It strikes me that jargon trips up audiences for similar reasons. It’s a burden for both experts and lay audiences alike to have to decode scientific information that contains a lot of jargon. Jargon or technical terms often don’t tell you much about the underlying objects, concepts or phenomena they represent. These terms are simply symbols that look like gibberish until you learn to associate them with what they represent. Often, a single term refers to a very complex concept or process with many steps: photosynthesis, mitosis, genetic sequencing. Every time you encounter a piece of jargon, you have to pull the related idea from memory to apply it. That’s a lot of mental work. But describing (or showing!) the meaning of the term instead, perhaps with imagery or metaphors, alleviates this mental load.

“Words and signs are merely the instruments to convey language. The language itself consists of ideas that are arranged in a way that is meaningful to the people using it. Words and signs are the things we use to convey those meanings to another person,” – Geoff Mathay

Now imagine English jargon translated directly into ASL. Upon seeing a technical term fingerspelled or created out of separate signs, an ASL user has added mental steps in decoding that jargon. But if that jargon is interpreted into a visual space that carries meaning, the dynamic movement of a process, or other information with it – the ASL user might be better equipped to understand and remember it than even a hearing person hearing the term in spoken English!

“The truth is that learning sign language enriches your cognitive processes and helps you develop higher abstract and creative thinking…” - Handtalk

In sum, I think there is a lot that science communicators can learn from ASL and the Deaf STEM community’s efforts to create meaningful iconic signs to communicate scientific terms and ideas. Any (hearing) science communicator can benefit tremendously from learning about the Deaf community and culture and even a bit of ASL!

Need more convincing? Check out the Atomic Hands Youtube channel, where Deaf scientists explain various scientific phenomena. Even if you don’t know ASL, the creative use of signing space and gestures referring to biological components within a cell in this video might help you better understand genetics!

“Sign language has a beautiful way of saying a lot in very compact gestures.” – Christina Goudreau Collison