The Cause(s) of Honey Bee Death

“Consensus is building that a complex set of stressors and pathogens is associated with CCD [Colony Collapse Disorder], and researchers are increasingly using multi-factorial approaches to studying causes of colony losses.” - Report on the National Stakeholders Conference on Honey Bee Health, USDA.

If you’ve been keeping up with the “what’s killing honey bees” news, you might be thinking: why can’t scientists agree on what’s killing these pollinators? I mean come on, is it pesticides? Fungicides? Viruses? A parasite? Bacteria? Cell phone signals? Climate change? Among online media headlines of “Scientists Confirm: ‘X’ kills America’s honey bees,” no wonder we get frustrated when the next article we see adamantly claims a different cause confirmed by science, or even the absence of a problem at all.

As is often the case in ecological and biological systems, what if there were no simple, single cause answer in the first place?

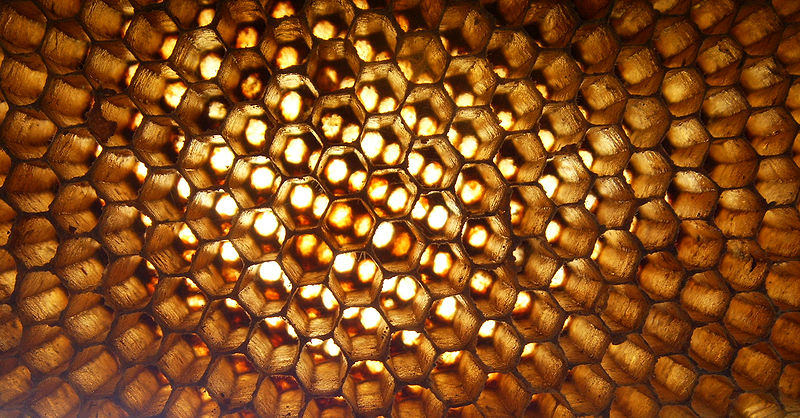

There is no doubt that we have a problem on our hands when it comes to the U.S. honey bee, Apis mellifera. These pollinators are extremely important to our agricultural industry as well as natural ecosystems. And since the year 2006, when unexplained losses of honey bee colonies began to be reported as Colony Collapse Disorder, beekeepers have been losing 30-90% of their honey bees every winter, losses that far exceed the historical rate of 10-15%.

But protecting our precious pollinators may mean understanding complex interactions between environmental factors, agricultural practices and naturally occurring honey bee pathogens.

“The problem is multifactorial: nutrition, pesticides, and pathogens.”

“Colony collapse disorder, when we came out with that phrase six years ago, was describing a very specific set of symptoms that pollinators were dying from,” said Dennis vanEngelsdorp, assistant research scientist in entomology at the University of Maryland and co-author of recent PLOS ONE research article demonstrating the effects of pesticides and fungicides on honey bee health. “Since that time, that term has been sort of co-opted to mean any unexplained colony death, which is never our intent. The truth is that we actually don’t see colony collapse disorder very much. But, we’re still losing 30% of our colonies every winter, which is an astronomical number.”

VanEngelsdorp and colleagues conducted experiments using real-world combinations and loads of pesticides in pollen collected by bees in the field, to determine the effects of these on healthy bees. The researchers collected pollen carried by honey bees returning to farm hives from their forages on almond, apple, blueberry cranberry, cucumber, pumpkin and watermelon crops. (Did you know all those crops required honey bee pollination?) After analyzing these pollen samples for pesticides and fungicides, among other chemicals, the researchers fed these pollen samples to healthy bees in a controlled environment.

The PLOS ONE study exists in a context of recent research studies suggesting that “honey bee diets, parasites, diseases and pesticides interact to have stronger negative effects on managed honey bee colonies” (Pettis et al. 2013). VanEngelsdorp and colleagues focused on the negative effects of pesticides in pollen combined with a naturally occurring species of single-celled parasite called Nosema.

“In our study what we did was went to bees that were pollinating different crops, and we collected the pollen that those bees were bringing back to the hive,” vanEngelsdorp said. “And then we analyzed that pollen for pesticide use, and then fed some of that pollen to newly emerged bees that we gave doses of Nosema, a common bee disease.”

VanEngelsdorp and his colleagues found incredible amounts of pesticides in the pollen they collected: an average of 9 different pesticides in each pollen sample, and as many as 21 different pesticides in some cases.

“But one product that really stood out was a fungicide," vanEngelsdorp said. "So bees that ate pollen samples that had some fungicides in them were twice as likely to become infected with Nosema, a fungal disease of bees, than those that were fed pollen that didn’t have this fungicide.”

According to vanEngelsdorp, the findings suggest that fungicides may have a sub-lethal effect on bees, and support the growing argument that there are many different factors coming together to cause bee colonies to decline. Fungicides used to prevent crop diseases could be affecting honey bees’ immune systems, making them more prone to infection.

“Nosema is a common adult bee pathogen,” vanEngelsdorp said. “It has certainly had been shown to be in colonies that have died from colony collapse disorder, but it's also been shown to cause colony mortality that isn't defined as colony collapse disorder.”

While Nosema and other known honey bee pathogens by themselves may not be causing the serious colony declines beekeepers have been observing, synergistic effects between these pathogens and fungicides, including the chemicals chlorothalonil and pyraclostrobin, could be. VanEngelsdorp and his colleagues observed other complex synergistic effects, too: fungicides made bees more susceptible to other pesticide chemicals, and chemicals used to keep mites away from crops also made bees get Nosema infections more easily.

“Here we have a fungicide that on its own, probably isn’t causing harm to bees, but in combination with Nosema, could be causing harm to bees," vanEngelsdorp said. "I think in the broader picture, it supports the hypothesis that there are many factors at play here.”

VanEngelsdorp says that while bees are still in trouble, most likely because of a combination of negative effects, his study might have some good news for beekeepers and farmers.

“There are things that we can do to help. One of the things, of course, is, that with other insecticides that are known to cause harm to bees, there are labels on them to prevent application when the bees are foraging on that crop. There’s no such label for fungicides, because we’ve never thought of fungicides as hurting bees. And so we should reconsider how we label fungicide use. And the second factors is that farm beekeepers can work with farmers to make sure that crops are being sprayed while the bees are foraging on those crops.”

Of course, research on the relationship been fungicides and honey bee pathogens remains to be done. For example, researchers don’t know why pesticides might make honey bees more susceptible to parasite infection. While it may have something to do with weakened honey bee immune systems and digestive tract disturbances, these are currently only speculative answers. But real-world studies like that published in PLOS ONE this month may provide better answers than single chemical laboratory experiments.

“We used real-world concentrations and real-world blends of products, and fed that to the bees,” vanEngelsdorp said. “And that’s very dirty data, because there are 9 different products on average in this pollen. And because these results came out of such dirty data, if you’d like, they’re even more convincing that something really is going on.”