Best Practices in Environmental Communication - A Scientific Paper

When it comes to communicating about environmental issues, it turns out we have a lot to learn from psychologists and audiences alike. Along with colleagues Zeynep Altinay and Amy Reynolds, I recently had a paper published in the journal of Environmental Communication, in which we used Louisiana's coastal crisis as a case study for best practices in environmental communication.

In our study, we interviewed communicators and psychologists, and surveyed Louisiana residents, in order to identify gaps in what we should be doing vs. what we are doing as environmental communicators. We found that both environmental psychologists and communicators emphasize knowing one's audience, telling local stories and building relationships with target audiences. We found that according to environmental psychologists and successful communicators, it is vital to avoid controversial terms and to focus on issues, impacts and solutions with which the target audience can relate.

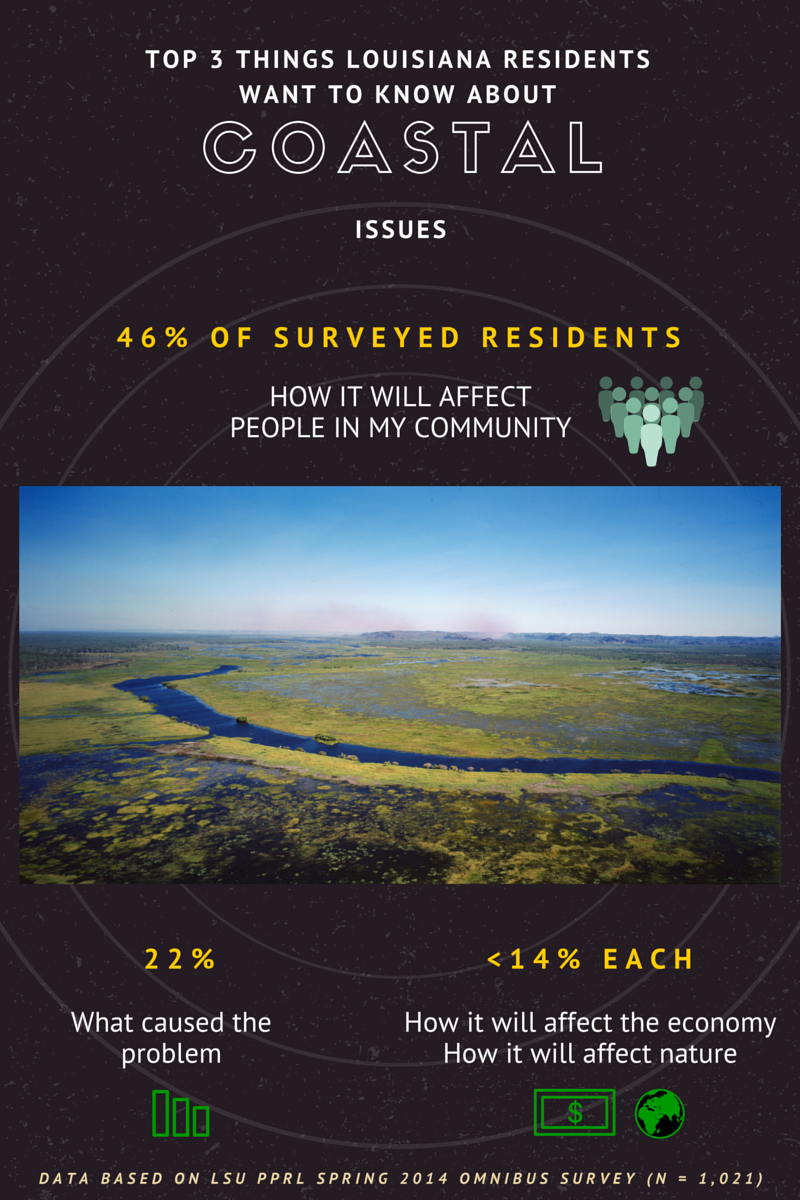

A representative survey revealed that Louisiana residents are most interested in hearing about how environmental issues such as climate change and coastal land loss are affecting their own communities. We conclude that environmental communicators everywhere could do a better job tapping into place attachment and sense of community among coastal residents to promote action.

Jarreau, Paige Brown, Zeynep Altinay, and Amy Reynolds. "Best Practices in Environmental Communication: A Case Study of Louisiana's Coastal Crisis." Environmental Communication (2015): 1-23.

The full paper, as it was accepted to Environmental Communication, is reproduced below as permitted by the publisher's guidelines. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis Group, in Environmental Communication on 30/10/2015, available online here.

Communication of complex environmental hazards and proposed solutions increasingly requires knowledge of local contexts, target audience concerns and values, and psychological principles (Clayton, 2012). Environmental communicators have increasingly realized that information-based communication strategies, especially those that ignore the role of values, routinely fail in promoting pro-environmental and resilient planning and behavior among key publics (Steg & Vlek, 2009). Yet, relatively few environmental communication researchers have pursued a rigorous integration of environmental psychology into strategic communication strategies implemented at local scales. We seek to fill this gap.

Applying environmental psychology concepts, this case study explores local as well as national communication efforts and identifies Louisiana resident information wants and needs. The intended audience of this research is environmental communicators in Louisiana and beyond. We hope environmental communicators will be able to incorporate the practical environmental psychology-based communication principles and local information needs that we identify herein into their messaging about coastal environmental issues.

We collected two sets of qualitative, in-depth expert interviews: first, with 10 local (Louisiana) and national environmental journalists and/or strategic communication experts; second, with 10 environmental psychologists from the USA, the UK and Germany. Both sets of interviews placed special emphasis on addressing environmental communication challenges in coastal Louisiana as a case study. Based on our interviews, we have identified an integrated set of best communication practices and strategies for promoting pro-environmental, resilient and sustainable behavior. We have also integrated public comments from the 2012 Louisiana Coastal Master Plan, a planning effort by the state’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority to save the Louisiana coast, to put current communication practices we identified in interviews with environmental communicators in a local case study context. Finally, we surveyed Louisiana residents, via a representative telephone survey, about their information needs related to coastal environmental issues. Survey results provide a practical context for the environmental communication best practices we identify.

Environmental Communication

Environmental communication focuses on the ways people communicate about the natural world and environmental affairs. Environmental communication as a field of study examines the public’s perceptions of the real world and how these perceptions shape human-nature relations. It examines the “role, techniques, and influence of communication in environmental affairs,” (Cox, 2010; Meisner, n.d., p. n.d.). The Working Party on Development Cooperation and Environment (WPDCE) defines environmental communication as “the strategic use of communication processes and media products to support effective policy-making, public participation and project implementation geared towards environmental sustainability” (WPDCE, 1999, p. 8). In order to develop effective environmental messages, communicators need to outline the objectives of the intended communication, identify stakeholders, define key messages and identify communication methods to disseminate information. We focus in this case study on identifying best practices in the formation and presentation of messages in a local context.

Environmental Psychology

Environmental psychology and conservation psychology address the relationships between people and their physical and social environments, including the impacts that people’s attitudes and behaviors can have on the well-being of local and global environments. Conservation psychology more specifically uses “the insights and tools of psychology toward understanding and promoting human care for nature,” (Clayton, 2012), where care for nature includes cognitive, affective and behavioral components (Clayton & Myers, 2011). Promoting a fundamental care for nature necessitates creating emotional attachment and helping people see how their behaviors effect environmental changes and in turn how environmental changes affect the things they value. Insights from conservation psychology can inform the work of environmental communicators. Yet, many environmental communicators remain relatively unaware of a growing body of psychological research related to sustainability and environmental conservation. Best practices informed by environmental psychology are applicable to wide array environmental communicators including journalists, scientists, members of environmental organizations and community leaders.

Promoting Pro-Environmental Behavior

Many current environmental problems are primarily a result of our choices and behaviors (Clayton & Myers, 2011). In this study, emphasis is placed upon messaging strategies that can ultimately mobilize environmentally significant behavior, including climate change mitigation and adaptation behaviors. Individuals and households control many climate-relevant behaviors (Dietz, Gardner, Gilligan, Stern, & Vandenbergh, 2009; Energy Information Administration, 2008), which include sea-level rise adaptation behaviors, such as choice of living location in coastal areas and adoption of flood control measures into new homes. And yet there has been little investigation into how environmental communicators in coastal regions could better promote mitigation and adaptation behavior (Whitmarsh, 2008). Environmental, social and conservation psychology research has identified many factors that can affect such behavior, including knowledge, attitudes, values, emotions, individual perceptions of efficacy and responsibility, social norms, feedback, prompts, reinforcements, goals and behavioral affordances (including physical and social barriers) (Clayton & Myers, 2011). Many of these behavioral factors are potential targets for communication-based interventions, if environmental communicators understand underlying psychological principles.

Information-Based Strategies

A long-standing tradition in environmental communication has been to provide lay audiences with information-based appeals to trigger pro-environmental concern and behavior. While more recent research has demonstrated the insufficiency of purely informational communication strategies (Whitmarsh, O'Neill, & Lorenzoni, 2011), a base amount of knowledge about the environment and environmental issues may be an important pre-requisite to sustained pro-environmental behavior. For example, action-based knowledge – or knowing specifically what one can do about environmental problems – is a necessary if not a sufficient condition for pro-environmental behavior (Kaiser & Fuhrer, 2003). Action-related knowledge, which “refers to behavioral options and possible courses of action,” (Kaiser & Fuhrer, 2003, p. 601) may be a stronger determinant of pro-environmental behavior than knowledge about the causes and implications of environmental issues in general (Smith-Sebasto & Fortner, 1994). Social knowledge, or the knowledge about the motives, intentions and behaviors of others toward the environment (Kaiser & Fuhrer, 2003), is also often crucial for pro-environmental action (Nolan, Schultz, Cialdini, Goldstein, & Griskevicius, 2008).

Value-Based and Targeted Messaging

Particular categories of universal human values that serve as guiding principles in people’s lives (Helbig, 2011; Schwartz, 1992; Steg & de Groot, 2012) have been shown to be important factors in individual’s motivations to engage in pro-environmental behavior (De Groot & Steg, 2009; Dunlap, Grieneeks, & Rokeach, 1983). Cultural worldviews that prioritize egoistic values such as achievement, power and hedonism, or that prioritize respect for tradition associated with political conservatism (McCright & Dunlap, 2011), have been associated with less positive engagement with the environment and downplaying of environmental risks (Corner, Markowitz, & Pidgeon, 2014; De Groot & Steg, 2008; Steg & de Groot, 2012). On the other hand, values including social and environmental justice, unity with nature, protecting the environment and broad-mindedness have been shown to predict more pro-environmental motivations and behaviors (Corner, Markowitz, & Pidgeon, 2014; Steg & de Groot, 2012).

Values can be incorporated in environmental messaging in several ways. The first is by taking into account the value orientations, worldviews and political ideologies of the target audience. The values we as individuals or communities already hold “influence how we interpret the information we are exposed to about climate change in ways that lead us to either accept or reject the need for greater engagement and action” (Corner, Markowitz, & Pidgeon, 2014). This concept is associated with targeted messaging strategies that depend on a clear and specific understanding of the target audience’s values and concerns (Maibach, Roser-Renouf, & Leiserowitz, 2009). Fundamental values can also be incorporated more directly in environmental messaging by framing campaigns or news coverage to emphasize values associated with pro-environmental action (Corner, Markowitz, & Pidgeon, 2014; Lakoff, 2008; Schultz & Zelezny, 2003).

Social Influence and Social Norms

A growing area of environmental psychology focuses on social influence and social norms, or how people tend to conform to the behaviors of those around them. Social norms consist of beliefs or perceptions about the common or accepted behaviors within a group (Cialdini & Trost, 1998). Regarding the presence of normative information in environmental messages, Robert Cialdini’s research highlights the “understandable, but misguided, tendency to try to mobilize action against a problem by depicting it as regrettably frequent” (Cialdini, 2003, p. 105). “Because people are highly guided by social comparison, they may choose to do as others are doing rather than to set themselves up as paragons” (Clayton & Myers, 2011, p. 9). Psychology researchers have shown that normative messaging highlighting pro-environmental social norms significantly promotes positive behavior toward energy use (Goldstein, Cialdini, & Griskevicius, 2008; Schultz, Nolan, Cialdini, Goldstein, & Griskevicius, 2007) and investments in ecosystem service protection programs (Chen, Lupi, He, & Liu, 2009), for example. These messages often produce positive impacts despite the fact that individuals often indicate on surveys that they are unlikely to be influenced by the actions of the people around them (Nolan, Schultz, Cialdini, Goldstein, & Griskevicius, 2008).

Based on the environmental communication and environmental psychology literature, we developed the following research questions:

RQ#1: What are the most important functions of environmental communication currently practiced in coastal Louisiana?

RQ#2: How can environmental communicators in coastal Louisiana better integrate lessons from environmental psychology?

RQ#3: Do communication strategies for coastal Louisiana that integrate lessons from environmental psychology match local residents’ information wants and needs?

Methods

Qualitative Interviews

In-depth interviews were conducted according to methodology laid out by Lindlof and Taylor (2010), using a “guided introspection” interview protocol (Drumwright & Murphy, 2004). In-depth elite interviewing “stresses the informant’s definition of the situation, encourages the informant to structure the account of the situation, and allows the informant to reveal his or her notions of what is relevant” (Dexter, 2006; Drumwright & Murphy, 2004). All interviews were semi-structured, took place either in person or via Skype/phone call, and were audio recorded for later transcription into text. General interview questions are presented in Appendix A.

A single, primary interviewer conducted in-depth elite interviews with local and national experts involved with communication of environmental issues. Interviewees included prominent journalists in Louisiana covering environmental beats. Interviews were subsequently analyzed based on two key aspects: functions and potential of environmental communication and effective environmental communication strategies. The interviewed experts are involved in professional environmental communication and represent government affiliations, journalism and academia. At the time of interviewing, they worked at local and/or national levels, focusing on outreach, education, and/or news reporting.

Five of the ten active environmental communicators interviewed were identified at the National Association of Science Writers (NASW) annual meeting in 2013; the remaining five participants were selected based on their influential role in the local community as knowledge creators. Among the 10 participants (5 female; 5 male), three participants were employed in local media, four in state agencies, one in academia, two in freelance writing. Interviewees included a Louisiana Sea Grant communicator, local environmental reporters from three major newspapers in Louisiana, an environmental journalism professor, an environmental communicator associated with the Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program, several communications and outreach personnel at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), several environmental science writers associated with NASW, and a writer at the Department of Energy Office of Science. Interviews focused on communicators’ self-perceived roles in environmental communication (i.e. objective reporter, or educator etc.) as well as messaging strategies they employ.

A single, primary interviewer conducted in-depth elite interviews with a total of 10 environmental, social and/or conservation psychologists from around the globe (4 female; 6 male). The final sample of psychologists interviewed were recruited via personal e-mail invitation, starting with interviewees prominent in the field of environmental and/or conservation psychology, followed by a snowball-based convenient sample of colleagues suggested by initial interviewees. Interviewees included a range of experts, from graduate scholars to senior faculty, of environmental psychology, social psychology, environment and behavior studies and ecopsychology representing universities in the USA, the UK Canada and Germany. All of our interviewees were individuals whom we believed could offer significant insights into the psychology and communication of coastal environmental issues in particular. Interviews focused on communication strategies to promote pro-environmental behavior, informed by environmental psychology.

All interviews, which typically lasted between 30 and 45 minutes, were digitally recorded, transcribed in full, and imported into AtlasTi for data analysis. Interview analysis was approached predominantly using inductive methods. For psychologist interviews, open coding was followed by selective coding once key categories and themes of best practices in environmental communication, based on principles of environmental and conservation psychology, had been identified. For communicator interviews, analysis involved open coding direct responses to particular questions on different themes: relationships and social structures, communication strategies and how participants defined their role in environmental communication.

Survey of Louisiana Residents

Questions related to Louisiana residents’ preferences for environmental issue coverage in their local media were included in the Louisiana State University Public Policy Research Lab’s (PPRL) Spring 2014 Omnibus Survey. The combined survey includes 1,042 respondents including 518 respondents selected from landline telephone numbers via random-digit dialing and 524 respondents selected from available cell phone blocks. Interviews were conducted from March 10 to April 6, 2014. The overall survey has a margin of error of +/- 3.04 percentage points. Survey questions were designed to be directly relevant to the environmental psychology principles uncovered in this study through qualitative interviews with environmental psychologists. See results section and Appendix B for survey questions.

PPRL Spring 2014 Omnibus Survey results were weighted by age, race, and gender to reflect current adult population demographics of the entire state of Louisiana as reflected in the 2012 Census Estimates. The final sample for survey questions presented here includes 470 men and 551 women (N = 1,021). The breakdown for race is 66% White, 25.3% Black and 8.2% Other. Participants vary in age from 18 to 65+, with older ages represented to a greater extent in this sample. A majority of participants has at least some college education (68.6%) and a majority is registered to vote in Louisiana (93%). Represented regions of Louisiana include Southwest Louisiana (n = 211), New Orleans area (n = 152), Baton Rouge area (n = 204), North Shore area (n = 171) and Northern Louisiana (n = 283).

Results

Environmental Communicators

Our first research question asks, “What are the most important functions of environmental communication?” The most frequently mentioned functions of environmental communication in this study included informing, communicating scientific reality and consensus, portraying science accurately and creating awareness among a non-technical audience. We also classified communication strategies under major theme categories identified through open coding: localizing the environmental issue at hand; building effective partnerships in communities; carrying out tailored and targeted communication; and, integrating environmental media framing. To place our findings in a local case study context, we have also integrated public comments from the 2012 Louisiana Coastal Master Plan into the results of our interviews with local and national environmental communicators described below.

Localizing the issue. One of the main goals of environmental communication is to help humans understand the natural world. Such communication ideally needs to establish a connection between the audience and its local environment, as explained by a majority of the environmental communicators interviewed in this study. One local journalist explained that local knowledge produces richer content because it collects information from “very well-versed” individuals and feeds that information back into the local community. This indigenous knowledge complements formal ways of knowing in environmental conservation by providing fundamental aspects of day-to-day interactions with the natural environment and showing how environmental change is interpreted by the local culture (Boven & Morohashi, 2002).

Because non-formal local knowledge, or "traditional ecological knowledge" (Bethel et al. 2011), is generally orally transmitted, local journalists become key players in documenting locals’ stories of land loss and its impacts, for example. These local stories of environmental changes can also be important pieces of otherwise incomplete local datasets for scientists documenting widespread environmental changes through traditional scientific methods, making it even more important for environmental communicators to connect with local residents in two-way dialogue (Bethel et al. 2014). Traditional ecological knowledge is “a cumulative body of knowledge, practice, and belief that evolves by adaptive processes, is handed down through generations by cultural transmission, and centers on the relationships of humans with one another and with their environment” (Bethel et al. 2011). Several local journalists explained that local stories are more likely to gather attention because they distill complex information into relevant and locally relatable examples, such as how coastal land loss affects local businesses or how hurricanes and floods sink roads.

Local messaging should also incorporate “real people” to communicate urgency. The term “real people” refers to talking about real life experiences to which lay readers can relate. This concept is also described in the journalistic community as personalization, and considered to be a fundamental journalistic norm in science communication (Boykoff & Boykoff, 2007). Personalization engages the public by downplaying big socio-political issues and emphasizing individual tragedies and triumphs (Boykoff, 2011). In our interviews, two respondents, employed at local news stations, explained that personal stories are especially interesting to write and interesting to read because the content connects with the audience. One journalist emphasized that stories about places and people who are affected by coastal crises such as an oil spill or land loss engage readers through passion and emotions. Crafting persuasive environmental messages, however, can be challenging even given the incorporation of local perspectives.

Building relationships. Environmental messages are particularly challenging because they need to address many issues regarding public policy such as social constraints, financial resources and rapid ecological transformation. One local journalist explained that residents often feel ignored by authorities. Building relationships with local partners based on mutual trust therefore becomes particularly vital to communicating complex environmental projects. Five interviewees described building strategic relationships with people in the local community as key to the success of planning, executing and evaluating environmental messages. For instance, one respondent, employed at a state agency promoting coastal resources, emphasized the importance of non-media partnerships with local elementary and high schools, commercial fisherman and state officials. Such partnerships are particularly important in resolving potential discrepancies among stakeholders, especially in places such as Louisiana, where the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people in the environmental decision-making is often subject to debate. For instance, public comments on the Louisiana 2012 Coastal Master Plan and media coverage (Lerner & Ollstein, 2015) of the threatened land probe environmental justice influences to communities, particularly Native Americans; and how overlooked partnerships can bring up grievances. Imbalanced relationships can raise issues of equality and justice that can hinder productivity among society members. Folger, Sheppard, and Buttram (1995) suggest that societal institutions and decision-making procedures should affirm the status of their members to restore trust and fairness.

Target-based communication. Journalists primarily write for a general public. The complexity and the large variety of environmental issues, however, have shown that this traditional top-down approach falls short in mobilizing citizens regarding many environmental issues. One interviewee explained the ineffectiveness of a “one-size-fits-all” approach in coastal environmental communication, which often results from the gap between academia and practice:

I have seen some bad presentations, where you have a researcher from campus talking to a group of fishermen, some of whom are Vietnamese. This particular researcher was trying to make an analogy talking about Whole Foods or Trader Joe’s and the retail experience you might have there, and there wasn’t anyone in the audience who may have had a point of reference about what they were talking about and you could see them drifting immediately (Environmental Communicator, Interviewee #1, Female).

Lack of trust toward authorities also appear in public comments in which residents characterize experts as ‘one of them,’ illustrating the importance of selecting experts who have experience, and credibility, in a given coastal community who can formulate messages for the audience to which they are speaking.

While environmental communication can involve communication with the lay public, it can also involve communication with policy advisers. The challenge is that policymakers are busy, generally not specialists in environmental issues, and may have conflicting sources of information. One communicator employed at a state agency explained that communicating with decision makers and policy makers requires short, clear and concise statements: “If you’re talking to a policy maker and you’ve got 30 seconds, get your three points out,” (Environmental Communicator, Interviewee #2, Male). As a remedy, experienced communicators present information in short formats, employing clear arguments and using simple language. One interviewee explained the most effective way to communicate science is not telling elected bodies what to do, but showing them options: “Based on the science this is your best option, this is next, this is third, all the way down to just doing nothing,” (Environmental Communicator, Interviewee #1, Female).

Language. Adapting the language of a message to simplify complex issues is a technique frequently mentioned by our environmental communicators. One communicator explained that she prefers using the phrase ‘sea level rise’ instead of ‘climate change’ when talking about coastal impacts, because unlike climate change, Louisiana residents can observe sea level change in the form of streets flooding or changes in tides. In this example, sea level rise provides a shorthand understanding of a complex environmental problem for coastal population by focusing attention on issues that the audience already feels are important, such as the loss of coastal land as a result of rising sea levels.

Environmental Psychologists

Our second research question asks how environmental communicators in coastal Louisiana can better integrate lessons from environmental psychology. We investigated this research question by interviewing environmental psychologists and asking them to apply their expertise to local communication strategies. In this analysis, we have divided openly coded themes into major and minor themes, based on how prominently psychologists mentioned the practices and strategies belonging to each theme. Major themes include codes mentioned by a majority of interviewees (at least 5 of 10). These include Targeted Messaging (81 quotations, 10 interviewees, see Figure 1); Action Knowledge (57 quotations, 11 interviewees, see Figure 2); Listening vs. Telling (46 quotations, 10 interviewees, see Figure 3); General Messaging Strategies (90 quotations, 9 interviewees, see Figure 4); Social Norms (35 quotations, 9 interviewees); and, Value-Based Messaging (38 quotations, 9 interviewees). Extensive interview excerpts representing the various major themes are available in Appendix C.

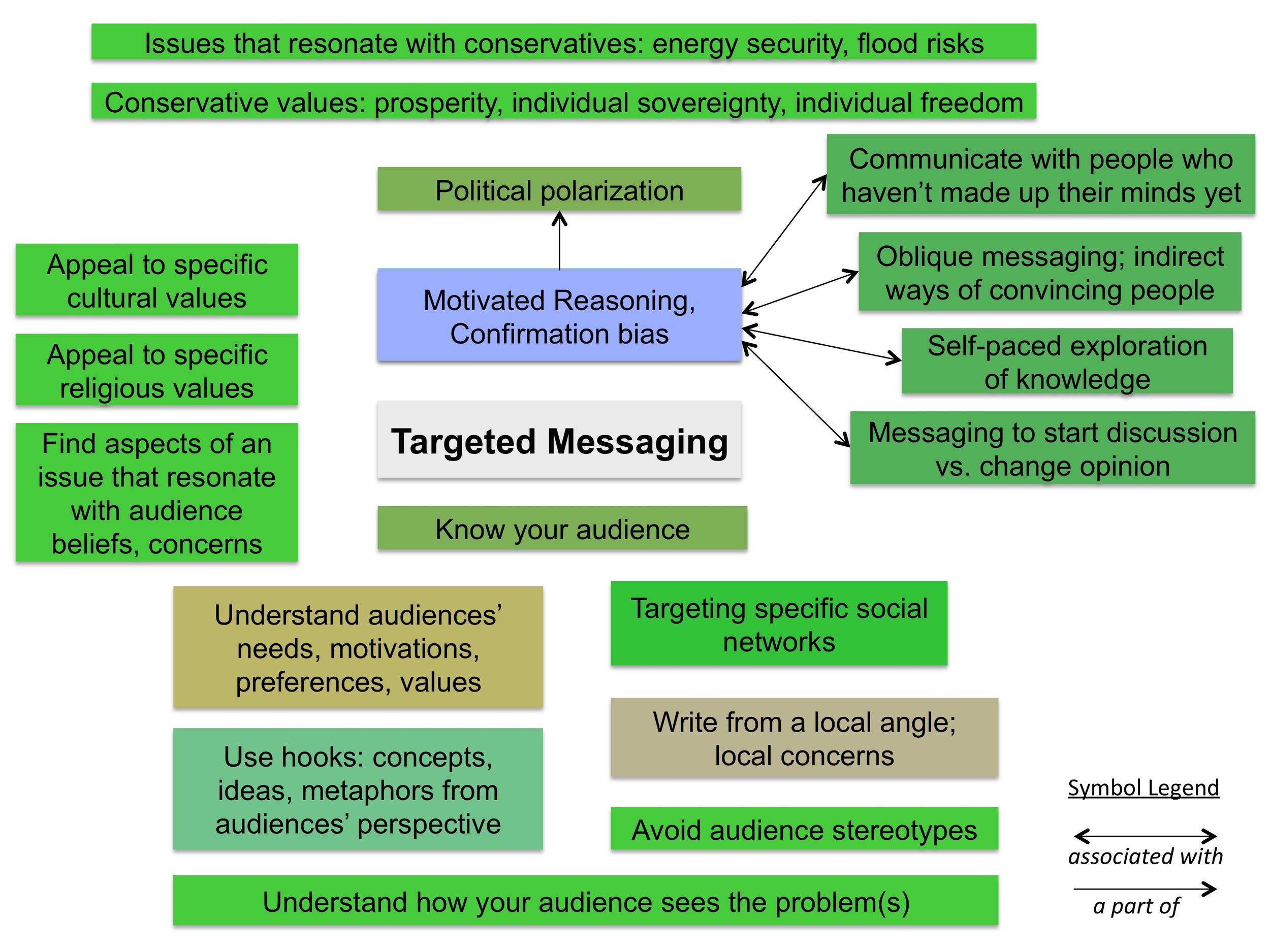

Major Theme: Targeted Messaging. Targeted messaging consists of knowing the audience, understanding the audience’s motivations, writing from a local angle and taking into account motivated reasoning and political polarization (see Figure 1). Interviewees identified targeted messaging as a necessary component of communication strategies aimed at diverse audiences and environmental behaviors. One psychologist identified this as the “Rubik’s Cube Problem”:

The problems that say a student faces in changing behavior is different from that of an old person usually. So from a pure research perspective, what you want is to figure out a message that fits one mini cube that fits which kind of person, which kind of behavior times which kind of problem that they have (EPsychologist#1, Male, Psychology and Environmental Studies, Canada).

Figure 1: Targeted Messaging Codes. Codes were auto-colored in AtlasTi to reflect relative groundedness (number of times a code is linked to a quotation) and density (number of times a code is linked to another code).

One prominent strategy for achieving targeted messaging of a known audience was identified as writing from a local angle and incorporating local concerns (12 quotations; 5 interviewees). The need to do so was explained by the fundamental tendency of humans to focus on the “Here and Now,” (5 quotations; 3 interviewees), or immediate and local concerns and observations. Several interviewees suggested that communicators point out environmental changes in terms of local animals, birds and fish, especially when communicating with audiences having pre-existing interests in these things, that is, fisherman and gardeners. This is a strategy distinct from highlighting global “canaries in the coal mine” such as the polar bear: “Polar bears are a nice little image, but they aren’t very persuasive because they’re too far away,” (EnviroPsychologist#1, Male).

Interviewees also suggested that audiences would be more likely to emotionally engage with local examples of environmental impacts, such as impacts to local communities. Messages that incorporate local examples narratives, especially messages “that talk about things that people can relate to like things they’ve personally experienced,” (EPsychologist#8, Female) are perceived as more vivid, more relatable, more compelling and more likely to promote positive action than messages that address environmental issues abstractly and/or on a global level. One environmental psychologist indicated that talking about local issues could trigger concepts of place attachment and place identity. Closely related is the concept of using hooks – concepts ideas, examples or metaphors, which can grab audiences’ attention by communicating environmental issues to which they can relate (10 quotations; 6 interviewees).

Another major theme related to targeted messaging is the need to understand needs, motivations and values (19 quotations; 9 interviewees). For example, based on a specific audience’s needs, motivations and values, communicators might be able to find and emphasize aspects of an environmental issue that resonate – and do not clash – with those needs, motivations and values. Examples include messages that take into account or appeal to particular political preferences (11 quotations; 5 interviewees), cultural values (8 quotations; 5 interviewees), or religious values (3 quotations; 2 interviewees). This strategy depends on communicators’ knowing their audiences through research and avoiding potentially misleading audience stereotypes.

Political polarization also arises as a prominent concern (11 quotations; 5 interviewees) related to the need to understand audiences’ motivations and values. For example, one interviewee (EPsychologist#8, Female) suggested that political conservatives respond better to environmental issues framed in terms of responsibility and frugality, while liberals respond better to the idea of caregiving and nurturance of the Earth. The problem of motivated reasoning (15 quotations; 5 interviewees), a process whereby individuals process information in a biased manner to reinforce their prior views (Kunda, 1990), was often mentioned in conjunction with political polarization. One interviewee in particular suggested that environmental communication has largely failed not primarily on account of jargon and complex technical topics, but because it has “failed to engage people who have a different initial opinion,” (EPsychologist#6, Male). In order to avoid having people reject environmental messages outright or filter messages in ways that reinforce what they already think or believe (Druckman & Bolsen, 2011), environmental psychologists suggested using the following strategies: avoid controversial, hot buttons, polarized issues and terms (9 quotations; 3 interviewees); allow for self-paced exploration of knowledge (4 quotations; 4 interviewees); use messages to start discussions instead of trying to change opinions (3 quotations; 3 interviewees); and, plant seeds of new concepts of the environment in people’s minds (5 quotations; 2 interviewees). One interviewee also recommended avoiding mention of climate change entirely and instead focusing on specific issues, such energy security and flood risks for political conservatives.

Major Theme: Action Knowledge. A second prominent theme that emerged from these interviews was that of Action Knowledge, which involves empowering people by showing them what they can do (see Figure 2). Major sub-themes related to Action Knowledge include empowerment (21 quotations; 5 interviewees); belief that one’s actions can help (8 quotations; 6 interviewees); knowledge of the consequences of one’s actions (8 quotations; 6 interviewees); and behavioral feedback (9 quotations; 5 interviewees). Minor sub-themes related to Action Knowledge include: a sense of personal responsibility (7 quotations; 3 interviewees); knowledge of specific action alternatives (8 quotations; 3 interviewees); and, confidence in one’s ability to act (3 quotations; 3 interviewees). These sub-themes and others visible in Figure 2 reflect the idea that people are more inclined to act if they know what they can do about a given problem, feel personally responsible for the problem, believe that their actions will help solve the problem, and are confident that they can actually carry out the required behavior (i.e. self-efficacy). Environmental psychologists recommended empowering people to take action on environmental issues through both individual-level and community-level communication strategies. For example, for individuals who are confused about appropriate actions or who might not have the confidence to do something, communicators might create messages incorporating specific action alternatives and “showing that it’s kind of easy, cost effective to do something,” (EPsychologist#13, Female). The knowledge of the consequences of one’s actions is an important pre-requisite to action – if one sees the negative (or positive) consequences of one’s behaviors, one is more likely to change one’s behaviors (or continue) to act in a pro-environmental way.

Figure 2: Action Knowledge. Codes were auto-colored in AtlasTi to reflect relative groundedness (number of times a code is linked to a quotation) and density (number of times a code is linked to another code).

Interviewees also recommended communicators help audiences visualize the impacts of their behaviors, for example by equating specific home energy expenditures in terms of AA-batteries – a more relatable unit than kilowatt-hours – or providing visual graphics of behavioral effects on the environment. Giving people very specific action alternatives to take, and providing feedback on performance, are also key strategies for empowering individual action. Another minor code mentioned in this context was to show immediate benefits of action and behavior change, particularly for those people not intrinsically motivated to act pro-environmentally (e.g. political conservatives). One interviewee suggested that for the later, benefits such as saving money, maintaining personal safety and living healthier can be strong action motivators.

Several interviewees suggested more community-based Action Knowledge strategies for empowering action. These include creating community-wide awareness of a need for action and empowering people by creating messages of community support. The idea is to create attachment to community values to work toward a shared goal: “[N]o individual is going to be able to change a lot of things, but individuals working together, coming up with shared solutions,” (EPsychologist #2, Male) can collectively solve problems. One way to achieve this community-based Action Knowledge was described as being solution-oriented, as opposed to problem-oriented: “here’s a problem and here’s something you can do and here’s why it will matter if we do it,’” (EPsychologist#12, Female).

Major Theme: Listening vs. Telling. As a result of considering people as active agents of change, several interviewees stressed the need to help audiences come up with their own solutions to environmental problems (5 quotations; 3 interviewees) and to foster “real” communities of action versus relying on simple “message hacks” designed to encourage action (See Figure 3; 1 quotation, EPsychologist#9, Female). To foster these communities of action, interviewees suggested that communicators should actively listen to their audiences. Through listening, communicators should understand how a target audience sees a given environmental problem (5 quotations; 3 interviewees) and what that audience’s needs, motivations and values are (19 quotations, 9 interviewees). By tapping into this deeper understanding of a target audience, one interviewee in particular suggested that communicators should be able to create messages that connect with people on a deeper level (4 quotations; 1 interviewee) and that people will be more likely to share with one another (3 quotations; 1 interviewee).

And the filmmaker is looking into people’s eyes […] and saying, ‘I can’t do this alone. I need you. I need you to make the world right because we can.’ And that’s not a social norm habit. That’s a real, deep, authentic form of community (EPsychologist#12, Female, Social Ecology, California).

Figure 3: Listening vs. Telling. Codes were auto-colored in AtlasTi to reflect relative groundedness (number of times a code is linked to a quotation) and density (number of times a code is linked to another code).

Major Theme: General Message Strategies – Making Message Vivid. A major sub-theme, related to General Messaging Strategies (see Figure 4), is making messages vivid, for example by using visual imagery (15 quotations, 6 interviewees). This code communicates the familiar concept that “a picture is worth 1,000 words,” and that people often connect more quickly and more emotionally with images than they do with text-based messages. Another related strategy is helping audiences visualize future environmental changes (3 quotations; 3 interviewees). One interviewee highlighted ongoing message strategies aimed at conveying “how one’s place is going to look different in the future because of climate change” (EPsychologist#6, Male) via vivid descriptions or visuals, especially interactive visuals: “People can engage and connect with that more easily and at the very least it can start a discussion” (EPsychologist#6, Male). Another interviewee referenced the Tidy Street Project highlighted in the documentary film Urbanized (urbanizedfilm.com/stream/), where a local street artist was commissioned to paint, for the duration of one month, the energy usage of several households on the pavement of the road outside their homes. A giant colorful graph painted on the street showed each household’s energy use compared to the city’s average. The success of the project in reducing household energy use (street's average energy use dropped by 15%) was a testament to the power of visual communication strategies, social norms and behavioral feedback.

Figure 4: General Messaging Strategies. Codes were auto-colored in AtlasTi to reflect relative groundedness (number of times a code is linked to a quotation) and density (number of times a code is linked to another code).

Minor Themes: Environmental Education, Barriers to Action and Storytelling. With the exception of a single environmental psychologist, interviewees generally rejected the information deficit model, or the idea that “people don’t understand what they don’t know about the environment and it’s really for us to communicate and tell people,” (EPsychologist#2, Male). Instead, most interviewees emphasized that it is generally other physical and lifestyle barriers to action (e.g. lack of public transportation, U.S. “car culture”, lack of financial resources, pressures to conform to a consumer lifestyle for political conservatives), not lack of knowledge, that result in low levels of pro-environmental behavior. Other barriers to action include feeling overwhelmed, often an undesired side effect of fear-based appeals in environmental messaging, perceived inequity or “why should I do something when those people in another country do nothing?” (EPsychologist#1, Male), uncertainty and perceived lack of control. Interviewees suggested several general messaging strategies (Figure 4), including storytelling and empowerment, that could help to overcome non-physical barriers to action.

Major Theme: Social Norms. Descriptive norms and peer pressure is a major code in this sub-theme (33 quotations; 8 interviewees). Injunctive social norms (8 quotations; 5 interviewees) and the need to highlight positive behaviors in normative messages (3 quotations; 2 interviewees) are also codes that belong to this sub-theme. All interviewees in this study highlighted to a greater or lesser extent the power of descriptive social normative messages in promoting simple pro-environmental behaviors such as recycling, supporting “green” policies, conserving energy, etc. The power of such messages was explained by the fact that “people like to following the crowd” (EPsychologist#6, Male). Environmental psychologists often suggested making greater use of social norms, by highlighting “normal” pro-environmental behaviors in a community, or even making a pro-environmental value a norm: “So, everybody cares about protecting their community, everybody cares about the fisheries that we rely on, or everybody loves nature and can take care of it,” (EPsychologist#8, Female). Several interviewees also pointed out that in leveraging social norms, it is important to highlight the positive or desired behaviors, not the negative ones. Social normative messages are typically more convincing if they describe the “normal” values and behaviors of other people that the reader identifies with, based on aspects such as political preference, occupation, local identity, etc.

Major Theme: Value-based Messaging. While targeted messaging strategies emphasize appealing to the specific concerns, motivations and cultural, religious and political values of target audiences (often by geographical location), several environmental psychologists also highlighted the importance of value-based messaging on a broader level. Environmental communicators can appeal to fundamental human values and broad “green” or environment-centered values in order to motivate pro-environmental concern and action. Interviewees mentioned several universal human values or concerns that environmental communicators could appeal to in their messages: personal security and safety (2 quotations), concern for one’s own home and community (2 quotations), family values – such as health and security of one’s children – (2 quotations), environmental justice (2 quotations) and meaning in life (1 quotation). Several interviewees also stressed the need to focus on activating environment-centered values over self-centered values. These values might include protecting the well-being of other people (altruistic values) or the well-being of the natural environment (biospheric values) (Steg & de Groot, 2012). Interviewees cited research in the field of environmental psychology showing that messages stressing biospheric values can promote positive environmental behaviors in one area (e.g. energy conservation) to “spill over” into other areas (e.g. recycling) (Evans et al., 2012).

Survey of Louisiana Residents

Our third research question asked whether communication strategies for coastal Louisiana that integrate lessons from environmental psychology match local resident information wants and needs. Based on interview data, we designed four questions for the annual Louisiana omnibus survey to determine the messaging needs and preferences of Louisiana residents (see full survey questions in Appendix B). Results indicate that when a long-term environmental problem occurs, Louisiana residents want to know most about how the problem will affect the people in their community (see Table 1). Women are also slightly more likely to want to know more about this aspect of environmental problems than men, as are self-identified Democrats (48.9%) over Republicans (42.5%), Blacks (50.3%) over Whites (44.7%), and those who own a home (48.3%) over those who pay rent (39%) – likely because those who own a home are more invested or permanently rooted in a given community.

Table 1. Note: Respondents were prompted to select one of these responses in answering the question, “When a long-term environmental problem occurs, such as climatechange, coastal land loss, flooding and so on, what do you want to know the most?”

In terms of perceived media performance related to information needs, 76.3% of those who want to know most about “how the problem will affect the people in my community” indicate that their local media is doing a good job giving them this information. On the other hand, 64.4% of those who want to know most about “what caused the problem” indicate the same. Local media outlets could do a better job giving residents information about what causes various environmental problems and how these problems affect people in a given community.

In terms of solving environmental problems (see Table 2), democrats (55.7%) are more likely than Republicans (42%) to want to know what government can do to address these issues, while Republicans (22.8%) are more likely than Democrats (16.4%) to want to know what their community is doing. Also, respondents under 34 years old are more likely to want to know more about what they themselves can do about these issues (to help solve or adapt) (37.7%) than respondents 35 years old and older (21.9%), and are less likely to predominantly want to know more about what government could do (43% for 34 and under, 52% for 35 and up). These results may be useful to communicators in targeting audiences with Action Knowledge messages.

Table 2. Note: Respondents were prompted to select one of these responses in answering the question, “In terms of solving environmental problems such as climate change, coastal land loss, and flooding, which of the following would you like to know most about?”

Only 53.7% of respondents who want to know most about what they personally can to help solve or adapt to environmental issues indicate that their local media is doing a good job in giving them this information. 61.2% of those who want to know most about “how the government can address these problems” and 67.3% of those who want to know most about “what my community is doing” indicate the same. These results reveal significant areas for improvement for local environmental communicators, especially in areas of Action Knowledge.

Discussion and Conclusion

The results of this mixed-method case study provide key insights for environmental communicators, especially communicators in coastal regions. We asked environmental psychologists to describe not only effective communication practices and strategies for motivating pro-environmental behavior, but to focus on strategies potentially most effective for coastal residents familiar with flooding, coastal land loss, hurricanes and diverse structural and lifestyle barriers to action. Psychologists emphasized writing from a local angle (see Figure 4) and taking into account reader concerns and motivations and value messaging to appeal to specific cultural and pro-environmental values (see Figure 1). They also emphasized actively listening to audience’s concerns (see Figure 3) and giving people specific action alternatives in order to empower them to act (see Figure 2). Central to Louisiana, psychologists emphasized appealing to an appreciation for nature and local wildlife, local pride and place attachment in motivating people to take action to protect their local environment and local communities.

In comparing the best practices we identified in our interviews with environmental psychologists to the current communication strategies mentioned by environmental communicators, we see several areas of improvement. Both psychologists and communicators emphasized knowing the audience, telling local stories, building relationships with target audiences and targeted messaging. Both psychologists and communicators also frequently mentioned general messaging concerns of source credibility, avoiding controversial terms and talking about issues, impacts and solutions that the target audience can relate to. In these aspects, local communicators seem to be largely following advice that environmental psychologists might give related to communicating about pressing environmental issues in coastal Louisiana. Yet, other communication best practices mentioned by environmental psychologists were completely missing from our interviews with local and national communicators. These include, most prominently, focusing on communicating action knowledge and using social normative messages to promote pro-environmental behavior. Value-based messaging techniques and appeals to local pride and place attachment also seem to be under-used by our environmental communicators, although they did mention the need to understand local culture and concerns. Thus, specific strategies we identify under the headings of action knowledge, value-based messaging and social norms seem to be key areas of improvement. This is especially true for environmental communicators who identify their primary function as changing behavior.

Placing the findings from our interviews in a local context, a representative survey revealed that Louisiana residents are most interested in hearing about how environmental issues such as climate change, coastal land loss and flooding are affecting their own communities. This finding supports the idea that environmental communicators could do a better job tapping into strong place attachment and sense of community among coastal residents to promote action. Empowering people by showing them what they themselves can do about environmental issues – a critical component of motivating pro-environmental action according to our environmental psychologists – also seems to be lacking in local media coverage of environmental issues, according to the perceptions of surveyed Louisiana residents. This is a strikingly complementary finding to our observation that the environmental communicators we interviewed rarely if ever mentioned the need to communicate action knowledge, while environmental psychologists we interviewed placed strong emphasis on this.

Several limitations of this study warrant future research. With only 10 environmental psychologist interviewees representing a vast array of research sub-disciplines, future studies might focus on identifying best practices for targeted messaging, value-based messaging, action-based knowledge messaging or “listening vs. telling” strategies from researchers specialized in these particular areas. However, considering that environmental and conservation psychology is a relatively young field of research, we believe we were fortunate to be able to conduct in-depth interviews with this many field experts. In the future, a more extensive survey of current local environmental communication practices could better identify areas for improvement, and follow-up surveys of Louisiana residents could test whether suggested best practices were being implemented successfully on a local level. Future research could also apply our findings to other environmental issues in other contexts/cases to see if different local environmental issues alter some of our findings.

References

Appendix G5a public comments. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.lacpra.org/assets/docs/2012 Master Plan/Final Plan/appendices/Appendix G5a PublicCommentsUniqFINAL_wTpg.pdf

Bethel, M. B., Brien, L. F., Danielson, E. J., Laska, S. B., Troutman, J. P., Boshart, W. M., ... & Phillips, M. A. (2011). Blending geospatial technology and traditional ecological knowledge to enhance restoration decision-support processes in Coastal Louisiana. Journal of Coastal Research, 27(3), 555-571. doi:10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-10-00138.1

Bethel, M. B., Brien, L. F., Esposito, M. M., Miller, C. T., Buras, H. S., Laska, S. B., ... & Parsons Richards, C. (2014). Sci-TEK: A GIS-based multidisciplinary method for incorporating traditional ecological knowledge into Louisiana's coastal restoration decision-making processes. Journal of Coastal Research, 30(5), 1081-1099. doi:10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-13-00214.1

Boven, K., & Morohashi, J. (2002). Best practices using indigenous knowledge. The Hague: Nuffic.

Bowman, J. P. 2002. Understanding persuasion. Retrieved from http://homepages.wmich.edu/~bowman/persuade.html

Boykoff, M. T., & Boykoff, J. M. (2007). Climate change and journalistic norms: A case-study of US mass-media coverage. Geoforum, 38(6), 1190-1204. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.01.008

Boykoff, M. T. (2011). Who speaks for the climate? Making sense of media reporting on climate change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chen, X., Lupi, F., He, G., & Liu, J. (2009). Linking social norms to efficient conservation investment in payments for ecosystem services. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(28), 11812-11817. doi:10.1073/pnas.0809980106

Cialdini, R. B. (2003). Crafting normative messages to protect the environment. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(4), 105-109. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.01242

Cialdini, R. B., & Trost, M. R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 151-192). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Clayton, S., & Myers, G. (2011). Conservation psychology: Understanding and promoting human care for nature. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell

Clayton, S. D. (2012). The Oxford handbook of environmental and conservation psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Corner, A., Markowitz, E., & Pidgeon, N. (2014). Public engagement with climate change: the role of human values. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 5(3), 411–422. doi:10.1002/wcc.269

Cox, R. (2010) Environmental communication and the public sphere (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

De Groot, J. I. M., & Steg, L. (2008). Value Orientations to Explain Beliefs Related to Environmental Significant Behavior: How to Measure Egoistic, Altruistic, and Biospheric Value Orientations. Environment and Behavior, 40(3), 330-354. doi:10.1177/0013916506297831

De Groot, J. I. M., & Steg, L. (2009). Mean or green: which values can promote stable pro-environmental behavior? Conservation Letters, 2(2), 61-66. doi:10.1111/j.1755-263X.2009.00048.x

Dexter, L. A. (2006). Elite and specialized interviewing. Colchester, UK: ECPR Press.

Dietz, T., Gardner, G. T., Gilligan, J., Stern, P. C., & Vandenbergh, M. P. (2009). Household actions can provide a behavioral wedge to rapidly reduce US carbon emissions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(44), 18452-18456. doi:10.1073/pnas.0908738106

Druckman, J. N., & Bolsen, T. (2011). Framing, motivated reasoning, and opinions about emergent technologies. Journal of Communication, 61(4), 659-688. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01562.x

Drumwright, M. E., & Murphy, P. E. (2004). How advertising practitioners view ethics: moral muteness, moral myopia, and moral imagination. Journal of Advertising, 33(2), 7-24. doi:10.1080/00913367.2004.10639158

Dunlap, R. E., Grieneeks, J. K., & Rokeach, M. (1983). Human values and pro-environmental behavior. In W. D. Conn (Ed.), Energy and material resources: Attitudes, values, and public policy. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Energy Information Administration. (2008). Emissions of greenhouse gases in the United States 2007. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Energy.

Evans, L., Maio, G. R., Corner, A., Hodgetts, C. J., Ahmed, S., & Hahn, U. (2012). Self-interest and pro-environmental behaviour. Nature Climate Change, 3(2), 122-125. doi:10.1038/nclimate1662

Folger, R., Sheppard, B.H., & Buttram, R.T. (1995). Equity, equality, and need: Three faces of social justice. In B. B. Bunker & J. Z. Rubin (Eds.), Conflict, cooperation, and justice: Essays inspired by the work of Morton Deutsch (pp. 261-289). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc. Publishers

Goldstein, N. J., Cialdini, R. B., & Griskevicius, V. (2008). A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(3), 472-482. doi:10.1086/586910

Helbig, A. (2011, September). The role of values in environmental behaviour. Paper presented at the 9th Biennial Conference on Environmental Psychology, The Netherlands.

Kaiser, F. G., & Fuhrer, U. (2003). Ecological behavior's dependency on different forms of knowledge. Applied Psychology, 52(4), 598-613. doi:10.1111/1464-0597.00153

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480-498. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480

Lakoff, G. (2008). Don't think of an elephant: Know your values and frame the debate. White River Junction: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Lerner, & Ollstein. (2015, January 22). These native american tribes are fighting to stop their land from literally disappearing. Thinkprogress. Retrieved from http://thinkprogress.org/climate/2015/01/22/3613714/disappearing-wetlands-native-american-tribes/

Lindlof, T. R., & Taylor, B. C. (2010). Qualitative communication research methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Maibach, E., Roser-Renouf, C., & Leiserowitz, A. (2009). Global warming's six Americas 2009: an audience segmentation analysis. Fairfax: George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication.

Meisner, M. (n.d.). What is environmental communication? Retrieved from https://theieca.org/what-environmental-communication

McCright, A. M., & Dunlap, R. E. (2011). Cool dudes: The denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Global Environmental Change, 21(4), 1163-1172. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.06.003

Nolan, J. M., Schultz, P. W., Cialdini, R. B., Goldstein, N. J., & Griskevicius, V. (2008). Normative social influence is underdetected. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(7), 913-923. doi: 10.1177/0146167208316691

Working Party on Development Cooperation and Environment (WPDCE). (1999). Environmental communication: Applying communication tools towards sustainable development [Working Paper]. Paris Cedex: OECD Publications. Retrieved from http://vvv.oecd.org/dataoecd/8/49/2447061.pdf

Schultz, P. W., Nolan, J. M., Cialdini, R. B., Goldstein, N. J., & Griskevicius, V. (2007). The constructive, destructive, and reconstructive power of social norms. Psychological Science, 18(5), 429-434. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01917.x

Schultz, P. W., & Zelezny, L. (2003). Reframing environmental messages to be congruent with American values. Human Ecology Review, 10(2), 126-136. Retreived from http://www.humanecologyreview.org/102abstracts.htm#schultzzelezny

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, volume 25 (pp. 1-65). San Diego: Academic Press.

Smith-Sebasto, N., & Fortner, R. W. (1994). The environmental action internal control index. The Journal of Environmental Education, 25(4), 23-29. doi:10.1080/00958964.1994.9941961

Steg, L., & de Groot, J. I. M. (2012). Environental values. In S. D. Clayton (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of environmental and conservation psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (2009). Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(3), 309-317. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.10.004

Whitmarsh, L. (2008). Are flood victims more concerned about climate change than other people? The role of direct experience in risk perception and behavioural response. Journal of Risk Research, 11(3), 351-374. doi:10.1080/13669870701552235

Whitmarsh, L., O'Neill, S., & Lorenzoni, I. (2011). Engaging the public with climate change: Behaviour change and communication. New York: Earthscan from Routledge.